The Talk

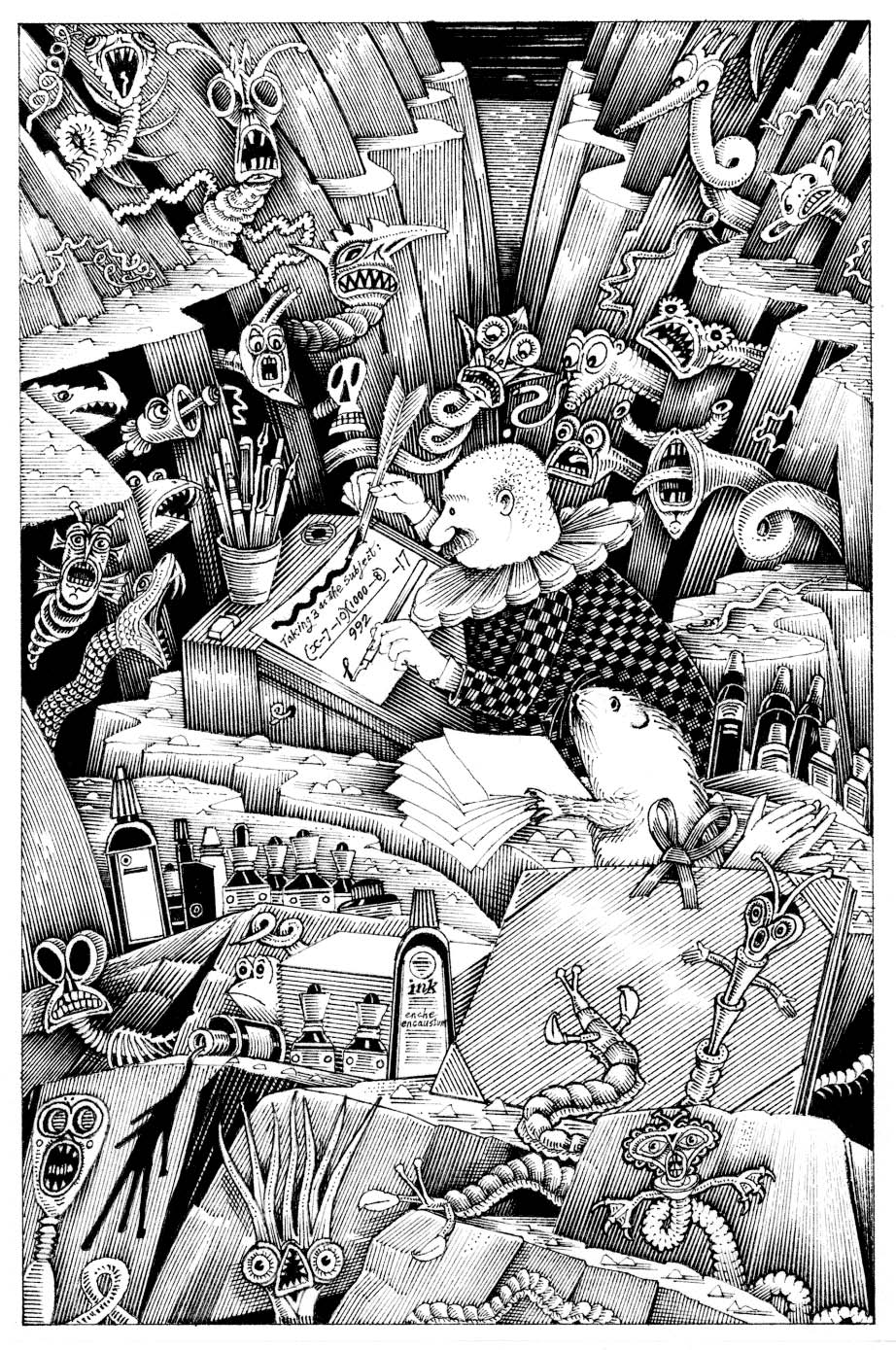

Nonsense is something that has always appealed to me and, having illustrated nearly every piece of Edward Lear’s nonsense verse, I have always felt a particularly urge to illustrate Lewis Carroll’s long ‘Agony’. When I first set out to illustrate the text I saw it as a dark narrative. Nonsense sometimes has the capacity of being apparently detached as if there is little emotional involvement. The stories are often told in a manner of nonchalant indifference. Both Lear and Carroll have that knack of appearing to be matter-of-fact in their poems. Nonsense is not necessarily funny, though it can sometimes be momentarily amusing by means of the language used and the unlikely situations that arise. I feel that there is something that underlies nonsense that gets to some kind of truth. Nonsense can sometimes be a mask for telling great truths as in fables. Fools and Jesters of old were masters of the art.

The language of rhyme and rhythm plays a crucial role in the direction in which a nonsense story enfolds. The destiny of the narrative often depends upon chance connections between rhyming words. The use of rhyme can sometimes lead the author to unexpected ideas. The repetition of like-sounds links one idea to another. The constraint imposed on the poet to come up with rhyming words does itself lead a narrative into particular directions. Rhyme and rhythm have the capacity to hold the interest of the reader and they also aid memory. Though it has its moments of humour The Hunting of the Snark is a bleak tale with very little optimism. Two of the crew come to sad endings. The Banker is left to his fate as he endures a fit of madness following his encounter with the Bandersnatch, and the Baker is lost altogether when he plunges into a chasm and apparently catches a momentary glimpse of a Boojum.

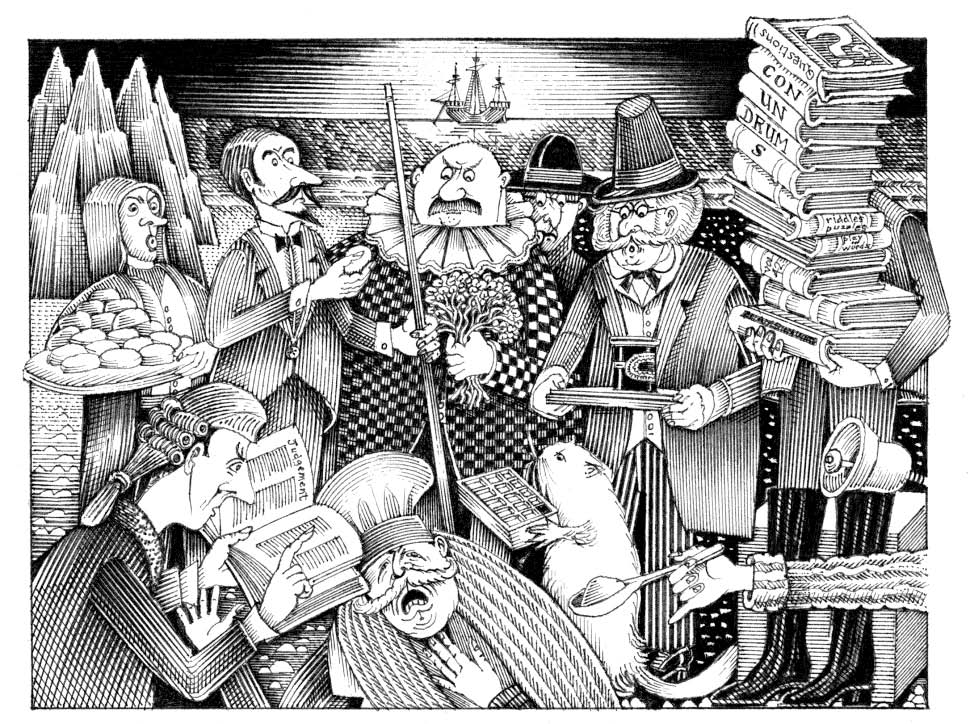

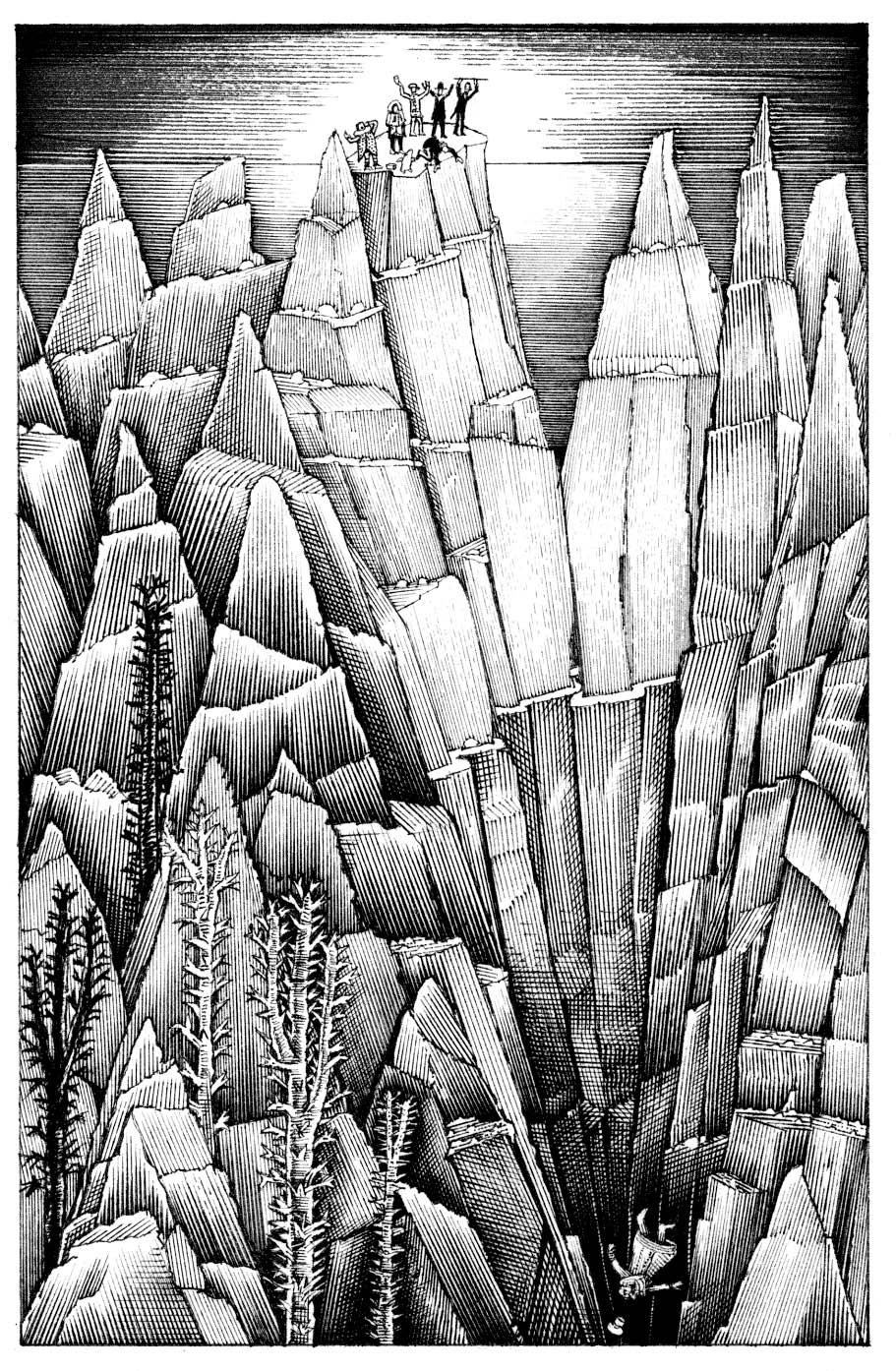

The Snark Crew (page 44/45) The Bellman, Bonnet-maker, Barrister, Broker,

Billiard-marker, Banker, Beaver, Baker, Butcher, and the Boots (click to enlarge)

Let’s have a glimpse of the cast of ten characters first – all beginning with the lletter B. The Bellman (leading the group here) shows stern leadership as captain of the crew. The only member of the crew that he appeared to be fond of was his pet apparently tedious though the crew was fond of his borrowed quotations. In short he seems to be a leader who possessed very few management skills. The Bonnet-maker, behind the Bellman, makes bonnets and hoods and likes to construct fancy arrangements of bows. We know little about the Barrister (the next in the queue) other than learning about his Kafkaesque dream about a court case that was ultimately conducted almost single-handedly by the Snark. The Barrister was essentially brought to join the crew in order to ‘arrange’ any disputes that may occur between the members during the voyage and the hunt. He also spent some time, for the benefit of the Beaver, citing ‘a number of cases, in which making laces had been proved an infringement of right’.

The next two are the Broker and the Billiard-marker, who hardly feature much in the story. The Broker (wearing a bowler hat) was appointed to value the goods and we know that the Billiard-marker had immense skill as well as having a penchant for chalking the tip of his nose. At one stage in the proceedings the Broker sharpened a spade at a grindstone with the enigmatic Boots (who we can just see as last in the line on the extreme right, holding a flag with the inscription ‘cura calceorum’ meaning ‘care of shoes’ or boots).

Some commentators have suggested that the Boots could have been the culprit who got rid of the Baker at the end of the story. When the Baker plunged into the chasm his last ominous words were ‘It’s a Boo-’, which could have referred to the Boots rather than the assumed Boojum. Did the Boots nudge the Baker off the crag to meet his doom? Was it in revenge for the Baker’s profligate habit of wearing too many boots? In my own illustrations I have included the Boots’s legs and boots only throughout the book, rather than include his whole figure, allowing him to be a somewhat enigmatic character.

Behind the Billiard-marker we can see the more prominent characters of the story – the Banker gripping a railway share, then the Beaver clasping a Pandora’s box of ‘Hope’, the Baker holding a bar of soap, and the Butcher with a carving fork. All the characters are smiling and have thimbles on their left index fingers. All are geared up for the hunt.

The Bellman’s handbell

We are told early on that the crew soon found out that the Bellman’s ‘only notion for crossing the ocean … was to tingle his bell’. And there are several instances of this. So, on each occasion when the Bellman rings his bell I have included an illustration of the bell within the margins of the pages in the book.

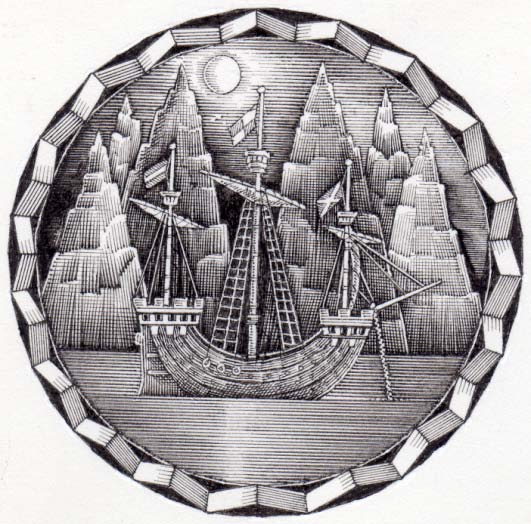

The Snark Hunters’ vessel in full sail (page iii) click to enlarge

This illustration of the Snark Hunters’ vessel in full sail appears as a preliminary image in the book, a kind of visual prelude to the beginning of the poem. It incorporates familiar symbols as an emblem. A ship, sailing in rough weather, suggests the danger of the voyage in the quest for the Snark. The anchor symbolises hope. Among the various practical agencies recommended to seek out a Snark, you’ll remember, was ‘hope’. Hope is also alluded to by the presence of a few stars in the sky. One of Alciati’s emblems entitled ‘Spes Proxima’ (hope is near) states that if ‘shining stars appear, then good hope revives the company’s lost courage’. The three signalling flags on the ship spell out the letters ‘Boo’, the first three letters of ‘Boojum’, an apparent sub species of Snark. The ship is sailing towards the darkness from the light, towards an unknown future. The circular view of the image suggests that someone is looking through a telescope. This may be the Snark itself. FN Andrea Alciati, Emblematum liber, Lyons, 1550.

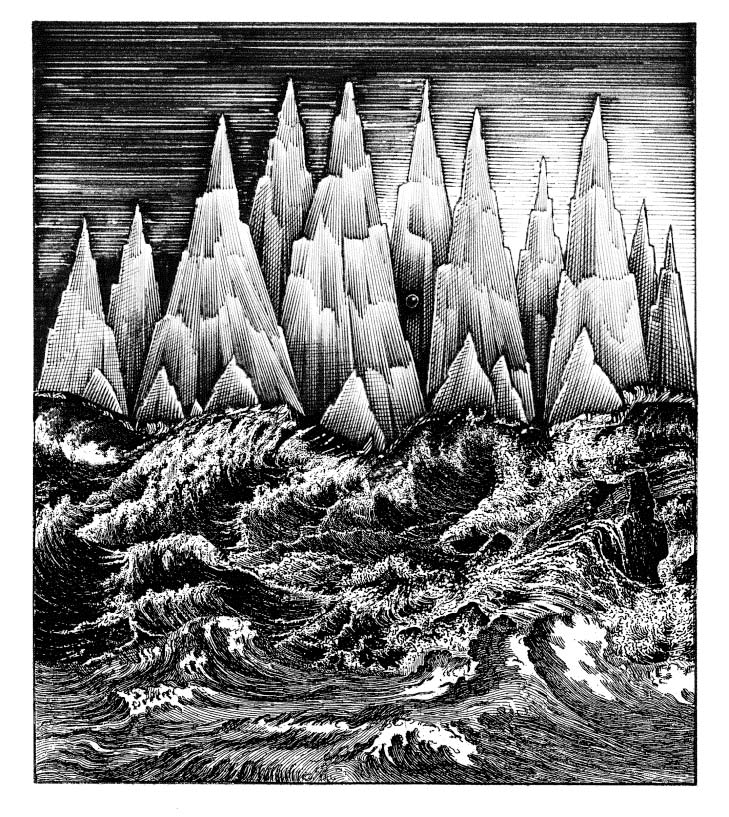

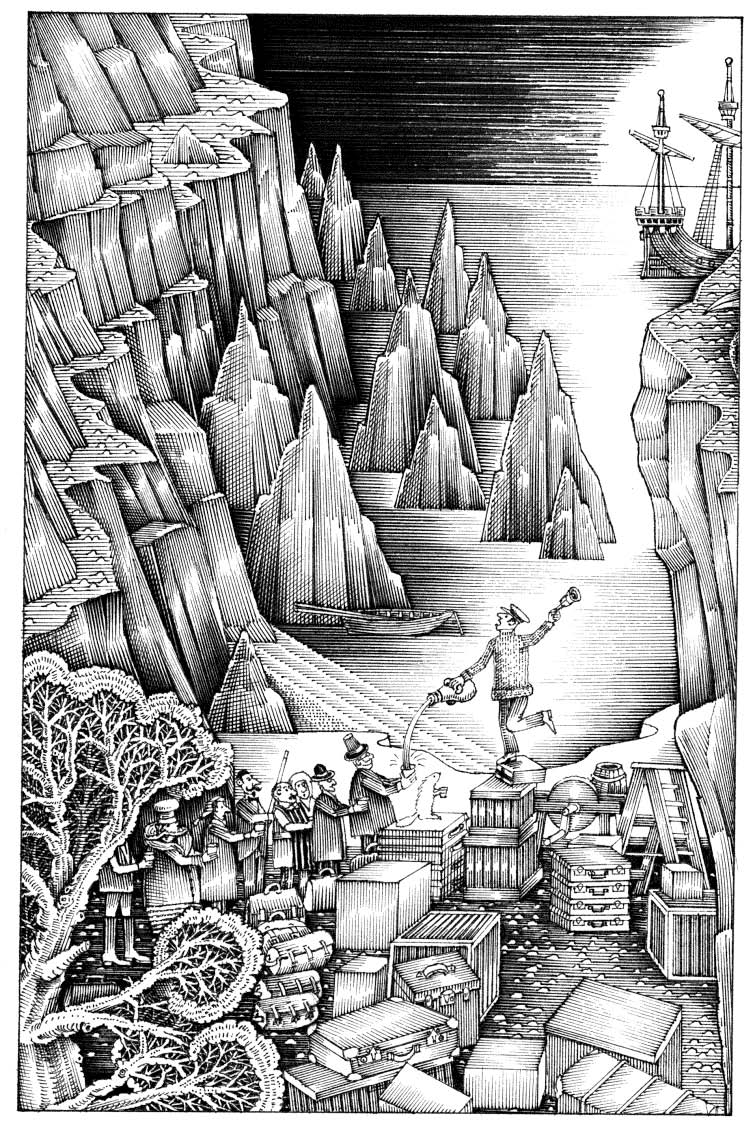

The craggy terrain of the Snark (page iv)click to enlarge

Here is the craggy terrain wherein the Snark is supposed to live, a notion of what the crew see as they approach the land in their vessel. It doesn’t take long to realise that the obscure word ‘Krans’ is the reverse spelling of ‘Snark’. A ‘Krans’ is aptly described as ‘a precipitous wall of rock overhanging a valley’. This is the very type of terrain where the Snark was supposed to dwell, one that (to quote Carroll) ‘consisted of chasms and crags’. The Collins English Dictionary similarly defines Krans as ‘a sheer rock face or precipice’. You might be able to see the eye of a Snark looking at us among the crags.

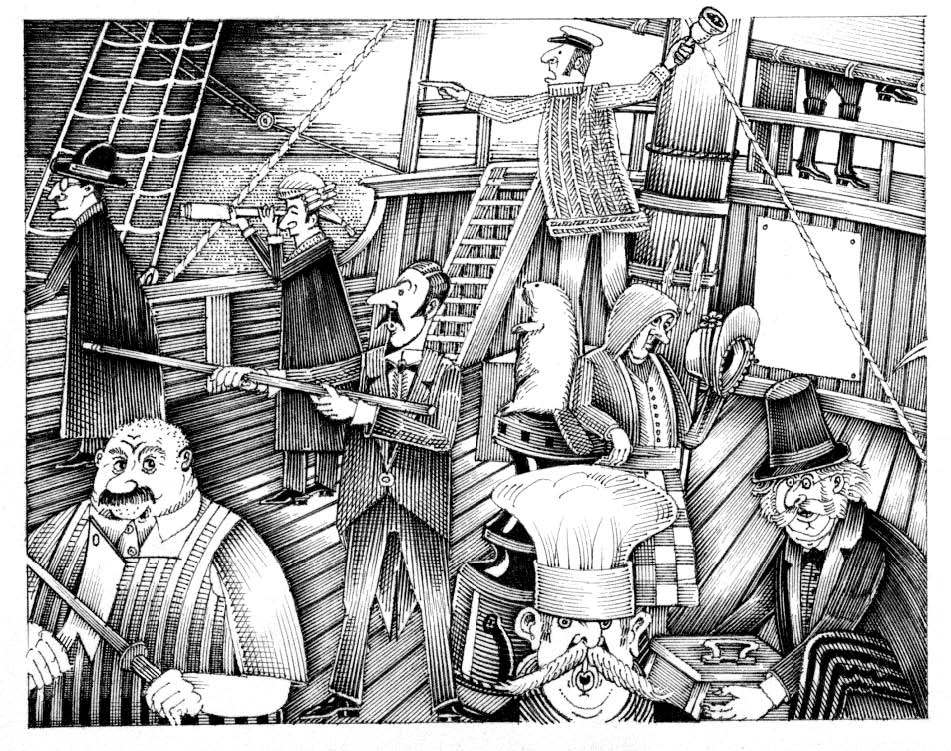

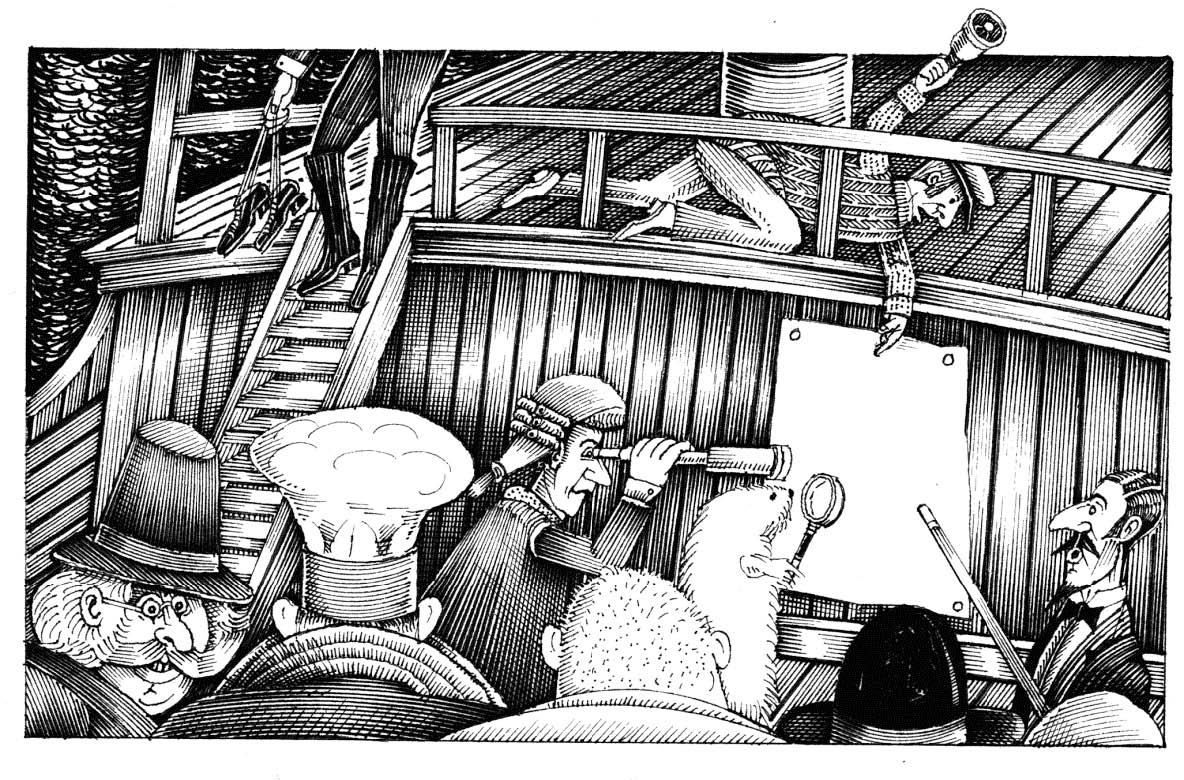

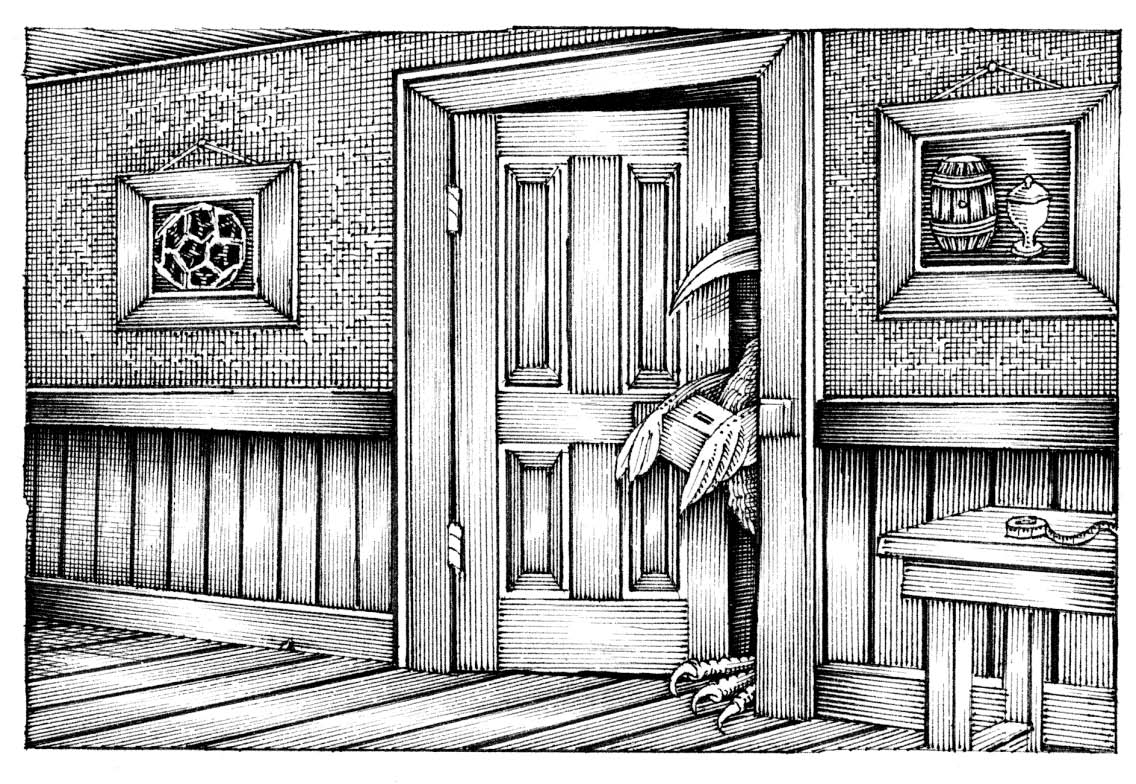

Members of the crew aboard ship (page 13) click to enlarge

This is the moment when the Bellman, the captain of the crew, cries out, “Just the place for a Snark” (at the beginning of the poem) when he spies land. The butcher on the bottom left is planning to kill the Beaver. You can see the blank map on the wall and above it on the upper deck we can see the boots and legs of the Boots who is holding a shoe. If you look carefully you can just see the beak of a Jubjub bird peering into the scene from the middle right hand side edge of the illustration.

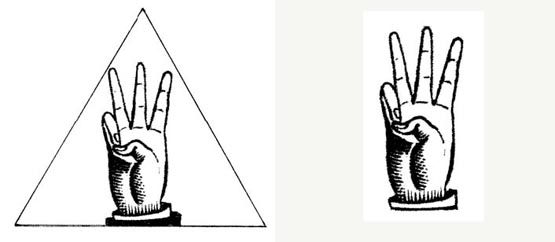

Two examples of three fingers indicating the number 3 (in a triangle on page 13)

plus several instances without a triangle)

I have placed a number of illustrations in the margins to act as indicators of a number of the author’s repetitions (we heard about the Bellman’s hand bell earlier). This has been done to provide a kind of visual index when these occur. Every time the number three is mentioned in the text I have alluded to it as an illustration of hands showing three fingers (on one occasion within a triangle). For instance, the number three occurs several times in the poem. I have therefore alerted the reader to these instances. In the second stanza The Bellman stated that he had said ‘Just the place for a Snark’ thrice. “What I tell you three times is true”, he insisted. You’ll remember that the Baker took it upon himself to wear three pairs of boots when he set out on the adventure. When the crew had landed they gave their captain ‘three cheers’ with their grog when he began his speech.

A beaver’s paw indicating the number 3 (page 35)

When the Butcher and Beaver went on their independent ‘sally’ they came across the sound of a Jubjub bird. The Butcher entreated the Beaver to keep count as he stated the call of the bird three times, its voice, note, and song. The Beaver struggled to keep count up to three (as illustrated here). This prompted the Butcher to give the Beaver an algebra lesson ‘taking three as the subject to reason about’. The length of time it took the Snark to speak at court (in the Barrister’s dream) was of course three.

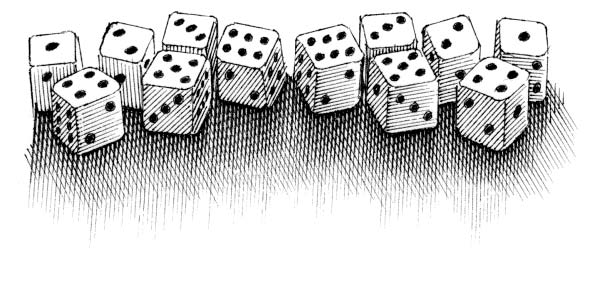

Twelve dice (the spots adding up to 42) (page 15)

Talking of numbers let us ponder upon the number 42. If the throw of two sets of six dice results in each set showing all the numbers from one to six face up, the sum of the twelve dice will add up to total of 42. Dice represent the risk of such a venture as a Snark hunting trip - a ‘dicing with death’ if you like.

Two hands signifying the number ‘42’ (page 15)

Here we have two hands signifying in hand language the number ‘42’, also depicted on the shirt cuffs in Morse code.

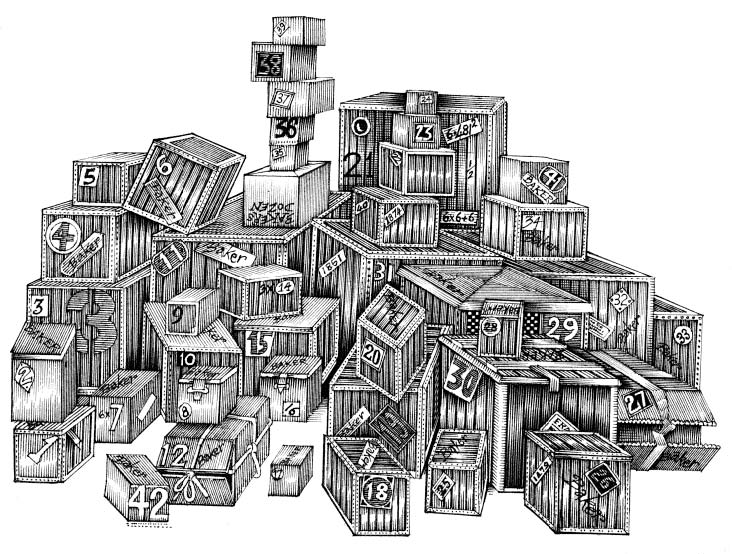

The Baker’s 42 boxes (page 15) click to enlarge

The number 42 occurs in the poem as the number of the Baker’s items of luggage when he set out on the quest, only to leave all his boxes behind.

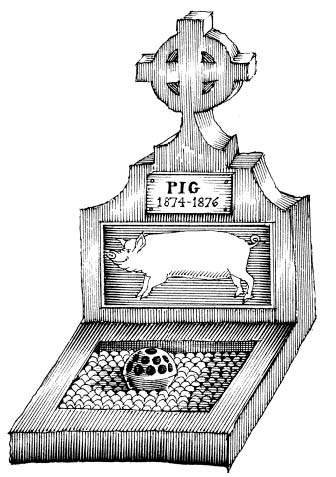

The pig’s grave (page 43) click to enlarge

So what is it about the number 42? Carroll was aged 42 when he first embarked upon writing the poem. If you add up the eight individual numbers in the two year dates when he worked on the book (1874-1876) you will soon realise that they add up to 42. These dates are registered on my illustration of the grave of the poor pig. The number forty-two became well known in Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. It was a number that was put forward as representing “the meaning of life, the universe, and everything”. This was calculated by a computer called Deep Thought, which had been asked to calculate the ‘Ultimate Answer’. The ‘number of the beast’ is said to be 666 and we find that 6 x 6+6=42. The binary number of 42 is 101010, which fluctuates alternately between ones and zeros. The well-known phrase – to be ‘at sixes and sevens’ means to be in a state of confusion or disagreement over something. In the poem there is a wonderful remark made by the Bellman about the confusion of the vessel when ‘the bowsprit got mixed up with the rudder sometimes’ causing it to be ‘snarked’. The Bellman’s navigational orders to the crew would be bound to place them all at sixes and sevens but there was little they could do about it. Six times seven equals 42 of course.

Carroll refers to this bewilderment and Rule 42 of the Bellman’s Naval Code in the original preface of The Hunting of the Snark. The number 42 also appears in Chapter 12 during Alice’s evidence in the trial of ‘who stole the tarts?’ in Carroll’s earlier book Alice In Wonderland. At one point the King of Hearts, ‘called out, “Silence!” and read out from his book, “Rule Forty-two. All persons more than a mile high must leave the court.”’

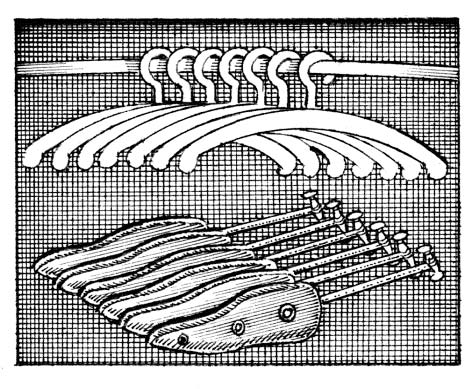

The Baker’s 7 coat hangers and 3 pairs of shoes (page 16)

We learn that the Baker had ‘seven coats on when he came with three pairs of boots’. This illustration is to show an association with coats and boots - coat hangers and boot stretchers - instead of the actual items themselves.

Candle end and toasted cheese (page 16)

The Baker’s intimate friends called him “Candle ends” while his enemies called him “toasted cheese”. Here I have turned the nicknames back into physical entities, trying to hint that both names suggest melting substances – be they given by friend or The Baker staring at a hyena (page 17)

The Baker was fond of joking with hyenas,

“returning their stare with an impudent wag of the head”.

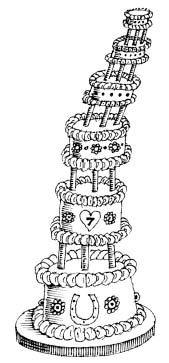

Bridecake (page 17)

The Baker seemed to be limited in scope as a baker, perhaps more a confectioner since ‘he could only bake Bridecake’, we are told. Hearts and horseshoes are conventional symbols on cakes and the 6-tiered cake here can be multiplied into the figure 7 that is inscribed on the heart of the cake to make 42. (The number seven alluding to the notion of marriage’s ‘7-year-itch!’)

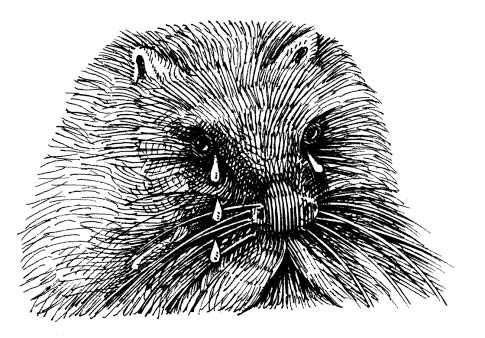

The Beaver weeping (page 18 and frontispiece)

Tears are shed on a number occasions during the search for the Snark. Here is the Beaver weeping when he hears that the Butcher ‘could only kill Beavers’. Later the Baker proceeded to tell a ‘story of woe’ in tears, either from a melancholy reflection or because the impatient Bellman told him to hurry up with his tale.

The Bellman telling the sobbing Butcher to ‘be a man’ (page 32)

At another point the Bellman rebuked the nervous Butcher, telling him to “be a man” when he heard him beginning to sob. The Beaver wept again when it struggled to count the call of the Jubjub bird, recollecting how easily he could do such sums in his youth. The Butcher’s tears were ones of delight when he realised that the Beaver had become a friend. During the court case it was a tearful jailer who informed the court that ‘the pig had been dead for some years’.

3 tears (page 18)

Drawings of tears are duly placed in appropriate places in the margins of the book when such instances occur.

The crew looking at the blank map (page 19)

The Bellman had brought a large map for the voyage ‘representing the sea, without the least vestige of land’. Here we have the crew looking at the blank map believing it to be ‘the best – a perfect and absolute blank’. You can see the anonymous Boots coming down the steps.

The Bellman serving out grog to his crew (page 21)

When they arrived on land they soon drank grog whilst the Bellman gave them a description of the Snark’s characteristics. The Jubjub bird can just be seen on the cliff below the galleon on the top right.

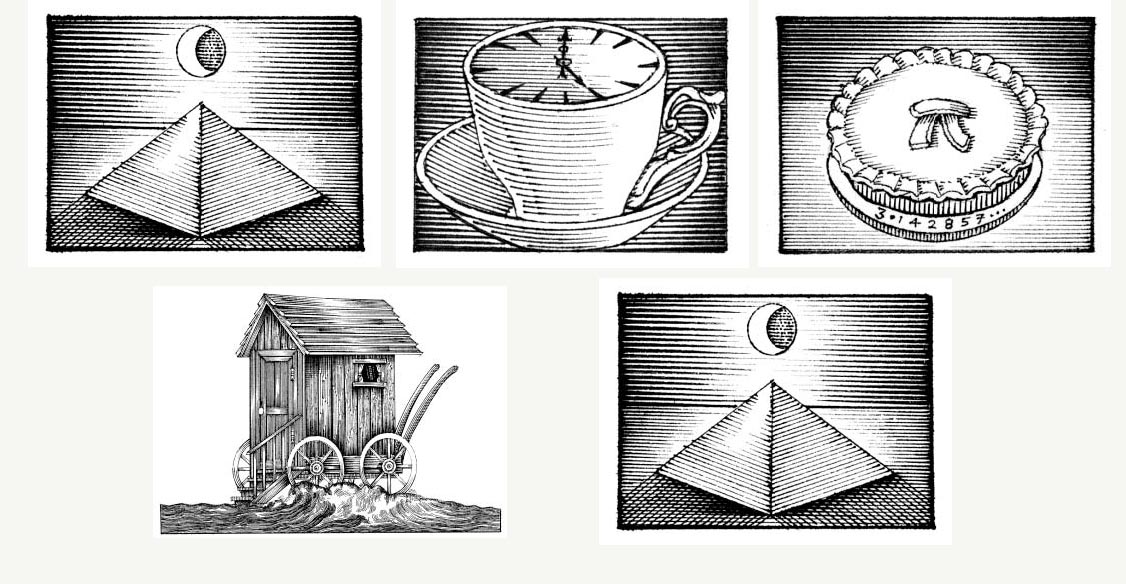

‘The five unmistakable marks’ of the Snark (pages 22 & 23)

In a speech the Bellman tells his crew that the five unmistakable marks of the Snark are: its taste; its habit of getting up late; its slowness in taking a jest; its fondness for bathing-machines; and its ambition. There are apparently different ‘batches’ of Snarks, we are told - some ‘that have feathers, and bite, and others ‘that have whiskers, and scratch’. It was important for me to place ‘The five unmistakable marks’ of the Snark on a double page spread so that the images are seen together and act as a mnemonic for the reader. For these I have drawn a notion of the Snark’s ‘hollow crisp’ taste as a hollow potato crisp. A cup of tea (with a clock face) signifies the Snark’s habit of breakfasting at 5 o’clock. For how the Snark might look gravely at a pun I have drawn as a pi sign on top of a pie. The Snark’s fondness for bathing machines is a straightforward image of one. The fifth mark of the Snark is its ambitious nature; hence I drew a pyramid; a notion of reaching towards the narrower top and reaching

for the moon.

The baker’s faint (page 24)

When the Bellman concludes his speech to the crew, he tells them that some Snarks may be ‘Boojums’, which caused the Baker to faint away. Here his passing out is depicted within a crosshatched rectangle. It attempts to depict that feeling of vagueness and the initial loss of sight and consciousness just as you are entering into a faint. We also learn from Carroll’s book Sylvie and Bruno Concluded FN, by the way, that Boojums had a tendency to wrench people out of their boots. The Baker was wearing three pairs of boots during the hunt, perhaps making him particularly vulnerable to a Boojum. Perhaps the Boots was vulnerable too .FN. Chapter 4 in Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno Concluded.

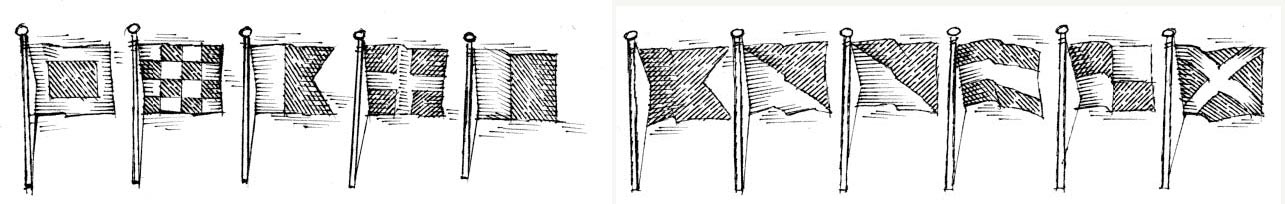

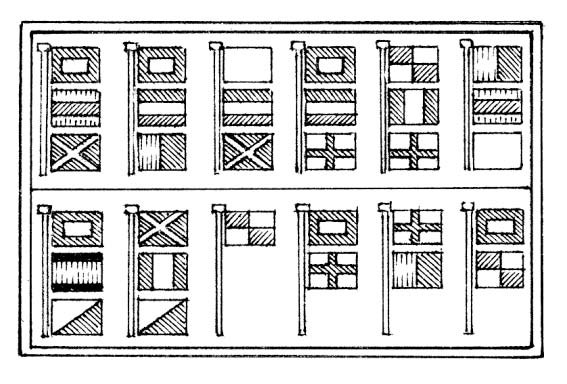

Flags signifying the word ‘Snark’ (page 24) and flags signifying the word Boojum’ (page 24)

Here we have an international flag-code illustration with signalling flags spelling out the letters for the words - ‘Snark’ and ‘Boojum’.

The crew rousing the Baker after his fainting (page 25

Here is the crew rousing the Baker after his fainting fit. They do so with muffins (served up by the Bonnet-maker and Billiard-marker), ice (presented by the Beaver who is clutching an ice box), mustard and cress (bunched in the left hand of the Butcher), jam (a jar of it held by the Baker on a tray and served up in a spoon by the Bellman whose arm can be seen stretched out from the bottom right hand corner) and judicious advice (pontificated by the barrister from a book). They also set him conundrums to guess, and, on the right, we can see the Boots hidden behind a pile of books, which he is carrying.

Hand pointing an index finger with thimble on it

The Baker’s uncle remarked to his nephew how the Snark may be sought, hunted, threatened and charmed with thimbles, care, forks, hope, a railway share, smiles and soap with the famous refrain:

“You may seek it with thimbles - and seek it with care;

You may hunt it with forks and hope;

You may threaten its life with a railway-share;

You may charm it with smiles and soap - ”

Each time these implements of hunting are mentioned, as a repeated refrain during

the course of the poem, I have highlighted these occurrences by including a drawing

of a hand pointing with a thimble-covered index finger.

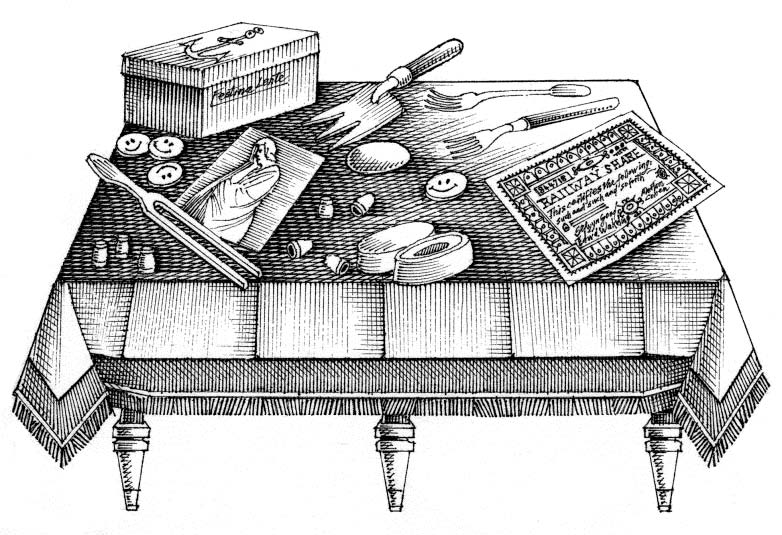

Implements to seek, hunt, threaten and charm a Snark (page 27)

Here, as a still-life on a table, we have the various agencies that are necessary to seek, hunt, threaten and charm Snarks. For those who know Holiday’s Snark illustrations they will perhaps identify my own use of his symbolic personification of ‘Care’ among the hunting utensils on the table on page 15. As for my representation of ‘Hope’ I have drawn a kind of Pandora’s box with an appropriate anchor symbol depicted on it. There are also a number of thimbles and forks (tuning fork, gardening fork and eating forks). There are also some smiley badges and bars of soap, as well as Good [acre], Edward Wakeling and Morton Cohen.

Flags signifying ‘England expects…’ (page 30)

Here is a group of flags representing Horatio Nelson’s famous signal “England Expects That Every Man Will Do His Duty”. (The Bellman alludes to this ‘maxim’ when he urges his crew to unpack and get ready for the fight). The signal was raised using Popham’s Telegraphic Code, which had been adopted by the Navy in 1803. This was made from the poop deck of the Victory at 11.15 am on 21 October 1805. This was just minutes before the beginning of the Battle of Trafalgar. I made a point of drawing this illustration precisely on the 200th anniversary of the event.

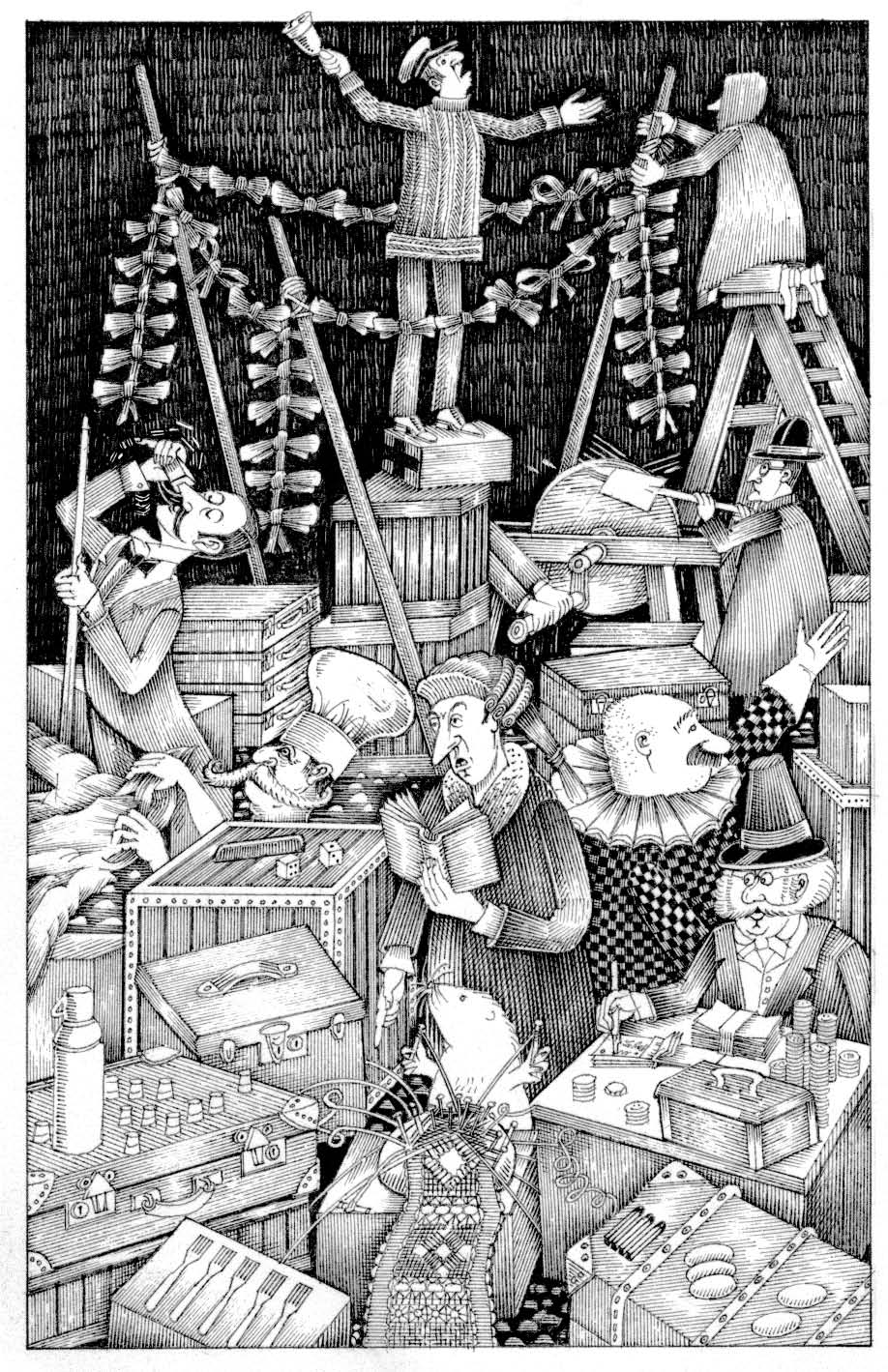

The crew rigging themselves out for the fight (page 31)

This is an illustration of the crew rigging themselves out for the fight. We see the Banker endorsing a blank check (which he crossed), and changing his loose silver for notes. The Baker is shaking the dust from one of his coats having carefully combed his whiskers and hair previously (as indicated by a comb situated close to him). The Boots (with just his forearms and hands showing) and the Broker are sharpening a spade with a grindstone and the unconcerned Beaver is making lace. The Barrister is trying in vain to appeal to the Beaver’s pride by citing a number of cases in which making laces had been proved an infringement of right. The Bonnet-maker is planning a novel arrangement of bows, while the Billiard-marker is chalking the tip of his nose with a quivering hand. The Butcher has dressed himself up rather finely, wearing yellow kid gloves (one which he is showing) and a ruff. Meanwhile the Bellman, standing on a box, is still muttering on and ringing his bell at the same time.

The Butcher giving the Beaver a lesson (page 37)

Here is the Butcher giving the Beaver a natural history and algebra lesson ‘with strange creepy creatures’ coming out of their dens.

The Jubjub bird collecting at a charity meeting (page 38)

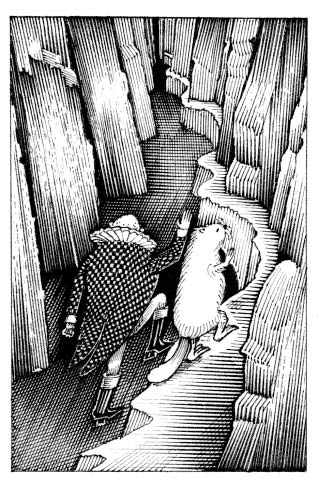

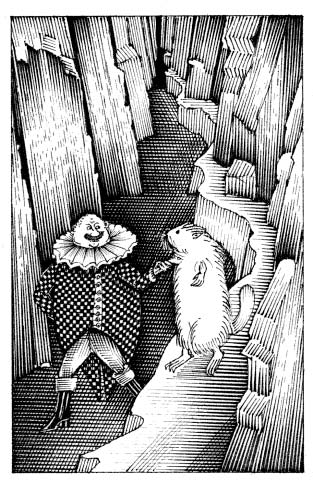

The Butcher and the Beaver marching along (page 34)

and later returning hand-in-hand (page 39)

If there is anything moving in the story it is the relationship that developed between the Beaver and the Butcher. Early on we are told of the Butcher’s limitations. He could only kill beavers, a considerable handicap for someone in the butchery business

and more so to join a group in which the boss’s pet was a beaver. Eventually in the story a bond develops between them as the Butcher gives the Beaver lessons in arithmetic and one in natural history. Even the Bellman is moved upon noting their warmer relationship when the two of them returned hand in hand from their exploit.

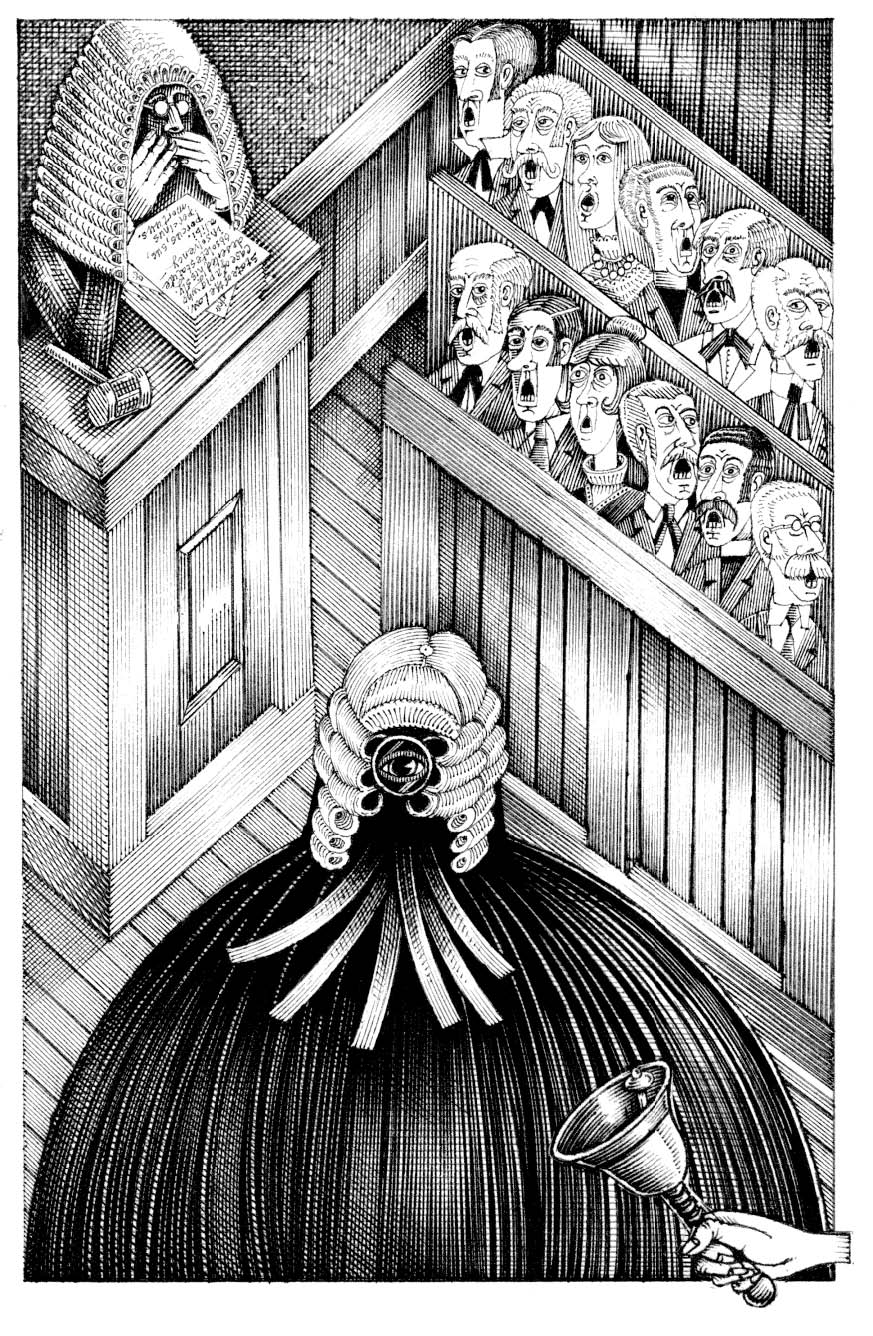

The Barrister’s dream of the court case (page 41)

The Barrister dreams of a court case in which the versatile Snark has a prominent role as defender of a pig who had deserted its sty: - as replacement judge in the case; and also as jury and pronouncer of the sentence. The Bellman’s bell at the bottom left is outside the picture to represent a waking-up reality as opposed to a dream.

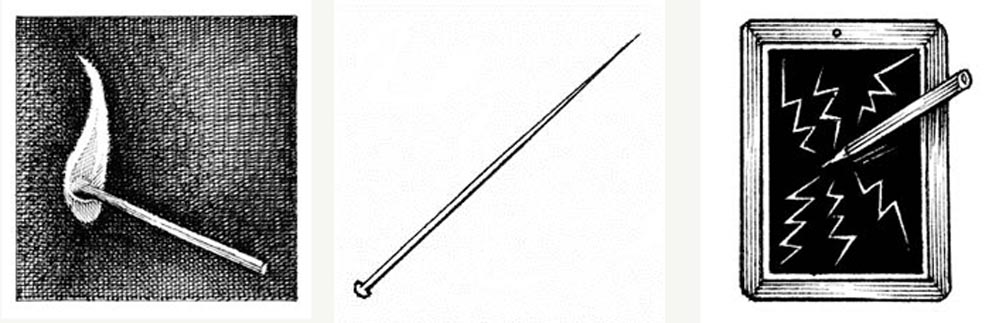

A struck match (page 26), the fall of a pin (page 42) and a pencil squeaking on a slate (page 34).

There are two or three instances when I have drawn illustrations that areessentially figures of speech. A match was not struck in reality on the Snark’s hide, nor did a pin actually drop when the Snark pronounced the pig’s sentence amid the hushed silence in court. I have thus illustrated these subjects in the spirit of nonsense. Similarly we are not able to hear the Jubjub’s voice but it reminded the Butcher of his school days – the sound of a pencil squeaking on a slate. And so we can see the sound of a squeak in the same way as the notion of a pin dropping.

.

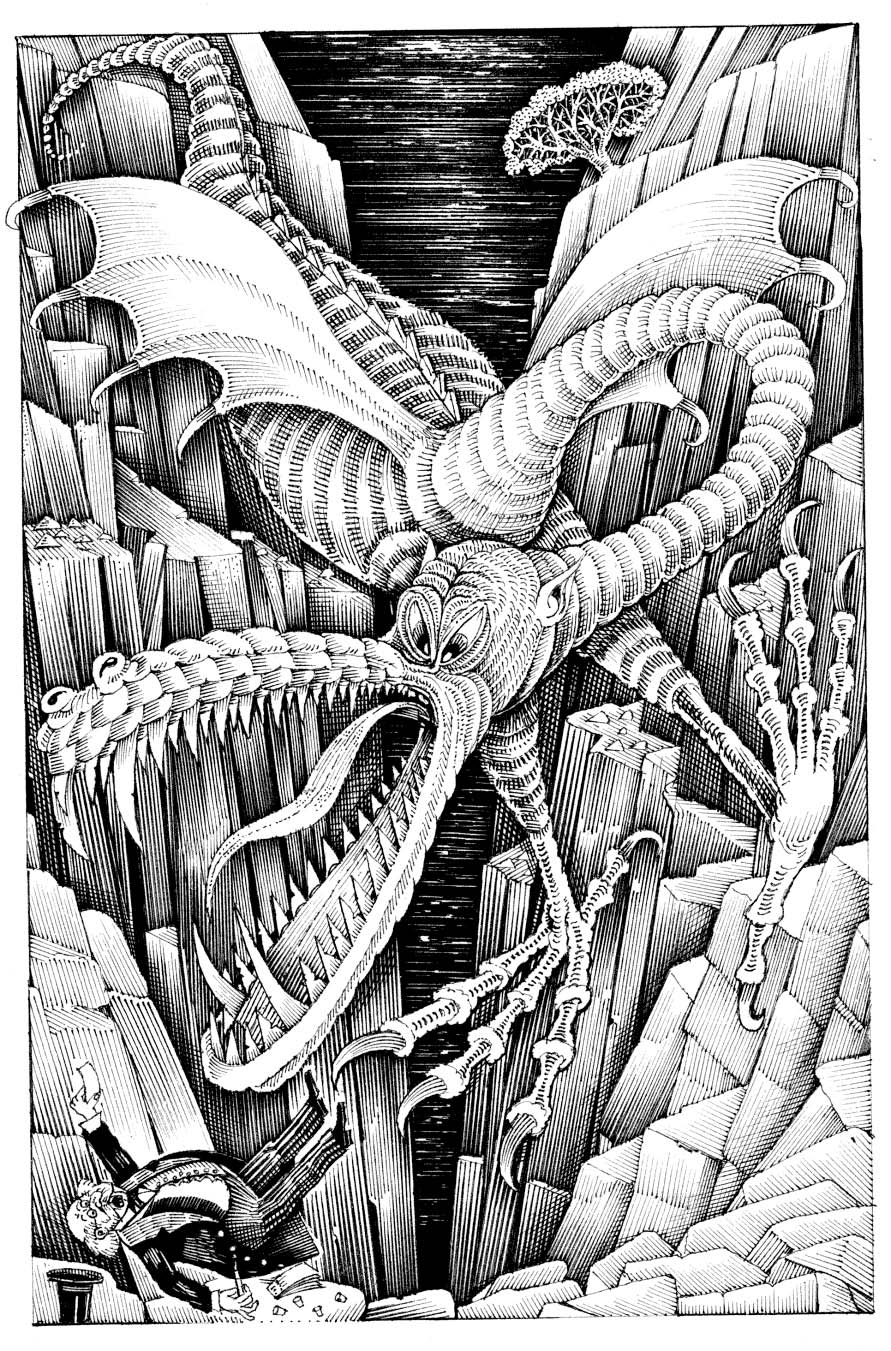

The Bandersnatch grabbing at the Banker (page 47)

Here we have a banded Bandersnatch snatching at the Banker, who is trying to bribe the creature to leave him alone with a cheque worth Seven pounds ten shillings. The appearance of a Bandersnatch (before we know if the crew will catch a Snark or not) is I believe a clever sleight of hand on the part of the poet. The introduction of a creature such as a Bandersnatch leads us into anticipating a dread that the Snark might be an even mightier creature. Our eventual not meeting up with the dreaded Snark or a Boojum later on comes as a kind of bathos, a let-down. A ludicrous descent from what we had eagerly expected to see at the end of the hunt.

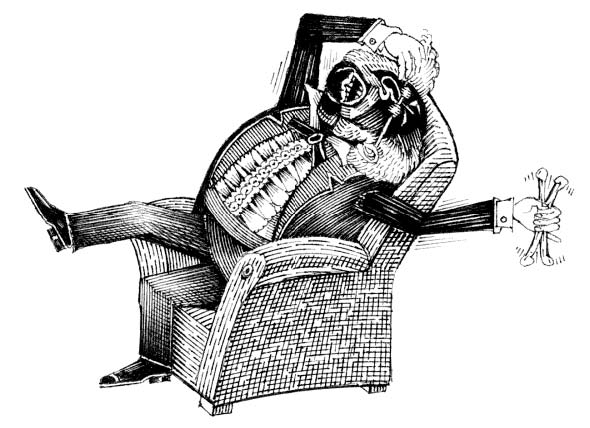

The Banker having a fit (page 48)

This is the result of the Bankers encounter with the Bandersnatch –having a fit, going black in the face, his waistcoat turning white, and rattling a couple of bones in his hands.

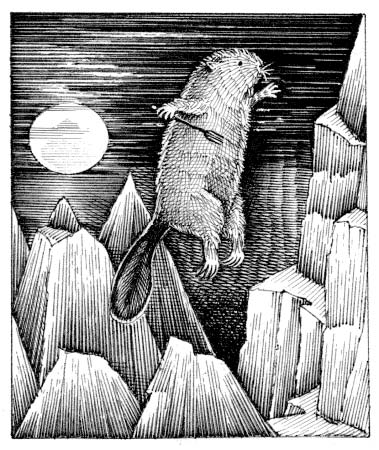

The Beaver bounding along on the tip of his tail (page 49)

during the final sally to hunt the Snark.

The Baker plunging into the chasm (page 50)

Then the Baker’s fall into the abyss. The Baker’s fate seems to be a ‘vanishing’, a disappearance into a void of nothingness. We are partly comforted by the fact that when he was trying to say his last words – “It’s a Boo-” he did so ‘in the midst of his laughter and glee’. Was this hysteria or joy? Perhaps what he saw was glorious. Whatever it was he disappeared. Reflecting upon the Baker’s ‘ominous words’ – “It’s a Boo -” makes me thing of a number of words that begin with the letters b, o, and o. Some have a resonance and a seeming appropriateness to the poem. The word ‘boo’ can be a word shouted out suddenly to surprise someone. A ‘boo-word’ can mean any word that seems to cause irrational fear. A ‘boob’ is a foolish person or a blunder. (I won’t refer the other meaning!) A ‘boo-boo’ is an embarrassing mistake. A ‘booby trap’ is a trap for an unsuspecting person, often intended as a practical joke. ‘Up the boohai’ is a New Zealand expression for getting thoroughly lost. To ‘boohoo’ is to sob. We also have a tree named after our mystery creature. A ‘Boojum’ tree is a deciduous one (Fouquieria or Idria columnaris), found in California. The common name of the Boojum tree was given by Godfrey Sykes, a plant explorer working in Tucson in Arizona. When he first saw the plant in 1922, he said, “It must be a Boojum”. The Spanish common name for this tree is ‘Cirio’, referring to its candlelike appearance. I have attempted to draw a version of these trees clinging to the craggy slopes when the Baker vanishes into the chasm. Mind you, I do not think the way I have depicted them would pass the scrutiny of a botanist. Not only is a plant named after a Boojum but also a musical instrument; a ‘Boojum’ being the anglicised version of ‘Buceum’ or ‘Butschum’; originally from the Latin ‘bucina’ meaning horn). It is a kind of long wooden alphorn used by Rumanian shepherds when calling in their cattle. Its melancholic sound was also employed in battle as well as being blown to signal a gathering. You can see a notion of the instrument depicted among the small illustrations in the end papers of the book. There are a number of archaic words that resemble the word Snark. ‘Snaar’ is a Cumberland word for greedy and ‘to snawk’ is a northern English word meaning to smell. One can only surmise that the Snark must have been greedy and smelly. The words ‘snare’ (as in trap again) and ‘snarl’ (as a vicious growl) are apt neighbouring words to ‘Snark’. There was no clue as to the Boojum’s identity as the Baker plunged into the abyss. The physical appearance of the Snark or Boojum is as enigmatic as any meaning that one would like to attribute to the poem itself. Retaining the mystery of what a Snark or a Boojum might look like is crucial to the story. The unknowingness leaves us in the air suspended. The very lack of physical identity of the Snark or the Boojum encourages us to look for meanings in the poem. You’ll recall that Carroll rejected the idea of having the Snark or Boojum depicted by his illustrator Henry Holiday in his first edition of the poem.

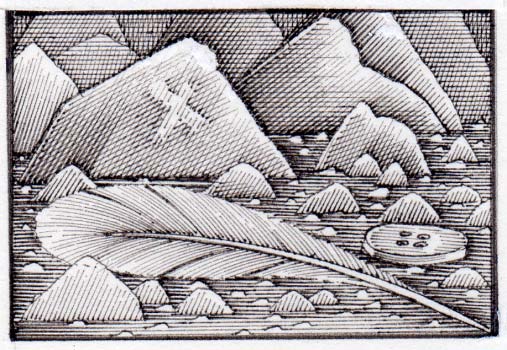

‘They found not a button, or feather, or mark’… (page 51)

After the loss of the Baker - the crew ‘hunted till darkness came on, but they found not a button, or feather, or mark, by which they could tell that they stood on the ground where the Baker had met with the Snark’. I thus drew the button, feather, and mark precisely because they didn’t exist.

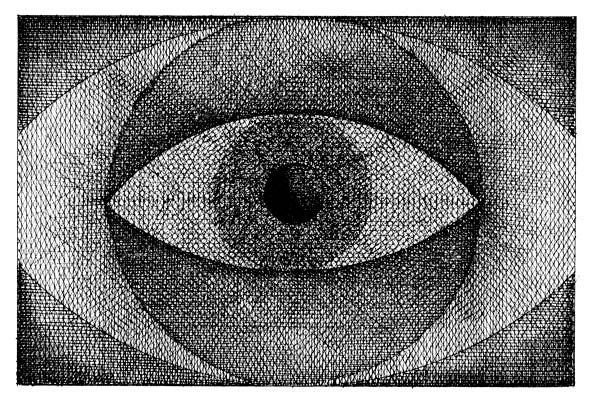

The ‘eye’ (page 52)

At the end of the poem I have drawn a kind of eye. This could be the eye of a Snark or a Boojum, or perhaps an ‘all-seeing eye’. It could be an image of interplanetary infinitesimal space. On the other hand the eye might belong to the Baker as he plunged into an unknown future. There is an eye within an eye as if they are absorbed within each other. We are told that eyes are the windows to the soul.

A blank square(page 52)

In the book there is a blank square situated below the eye, a representation of nothingness, the disappearance of the Baker, and perhaps a memory of the blank map that the Bellman brought with him for navigating the whereabouts of the Snark. Maybe it suggests that we enter an empty void of nothingness when we are dead. Perhaps the Snark or the Boojum were figments of the crew’s imagination and ours. In the final edition of the book it has been placed exactly 42 millimetres from the drawing of the eye, of course! Opposite this page in the book itself is a blank page.

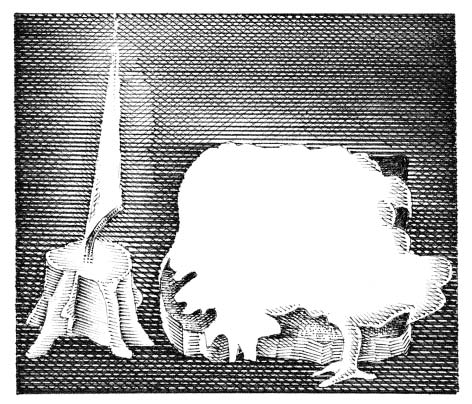

The Snark hunters’ vessel at anchor (page 54)

Then finally, as a kind of postscript, we have the Snark hunters’ vessel, anchored and becalmed in the stillness of the moonlight with a craggy mountain landscape in the background. It represents a kind of gloomy aftermath, a postlude or epitaph. The three signalling flags are at half-mast, out of respect for the Baker’s untimely disappearance that might have been his ‘death’. They spell out the letters ‘jum’, being the last part of the incomplete word ‘Boojum’. The moon is a symbol of change and growth. It also symbolises the passing of time and the passage from life to death, as well as resurrection. It is also associated withdreams, the unconscious and madness. The full moon stimulates the nocturnal activity of unseen creatures. ‘It’s all moonshine’ is an expression, meaning ‘it is all bunkum or nonsense’. ‘To cry for the moon’ is to crave for what is out of reach and ‘to aim at the moon’ is to be very ambitious. It will be recalled that the Bellman instructed his crew by telling them that the fifth and final mark to recognise a Snark was its ambition. The crew’s quest to find the elusive Snark, that turned out to be a possible Boojum, was also ambitious. In other words the notion of ‘reaching for the moon’ seemed to me to be an eminently suitable feature to include in the picture’ and the right way to finish off the book.

© John Vernon Lord (November 2006

Any enquiries about John Vernon Lord’s illustrated edition of The Hunting of the Snark should be addressed to Dennis Hall, The Foundry, Church Hanborough, Oxford OX29 8AB (Telephone 01993 881260). It has been published alongside a companion edition entitled All the Snarks by Selwyn Goodacre, which is an exploration and checklist of most of the illustrated editions of The Hunting of the Snark.

John Vernon Lord was born in Glossop, Derbyshire, in 1939. He studied at Salford School of Art and the Central School of Art and Design in London. In the early 1960s he began his career as a freelance illustrator, carrying out commissions that covered a wide spectrum of work for books, magazines, and advertising. Since the early 1970s he has written and illustrated a number of children’s books, which have been published widely and translated into several languages. His picture book The Giant

Jam Sandwich has become a classic, having been in print for thirty years. Lord’s prize-winning book The Nonsense Verse of Edward Lear was published in 1984 and his illustrations for Aesop’s Fables won the V & A/W.H Smith Illustration Prize in 1990. He has recently contributed illustrations to three Folio Society’s editions of Myths, Sagas and Epics. John Vernon Lord has also had a career in education having been Head of various departments and schools during his 38 years teaching at Brighton. He was Professor of Illustration at the University of Brighton 1986-99, where he is now Professor Emeritus. He was the chair of the Graphic Design Board of the Council for National Academic Awards 1981-84. |