back

AARON BOHROD

| DE WITT COUNTY June 1940 | |

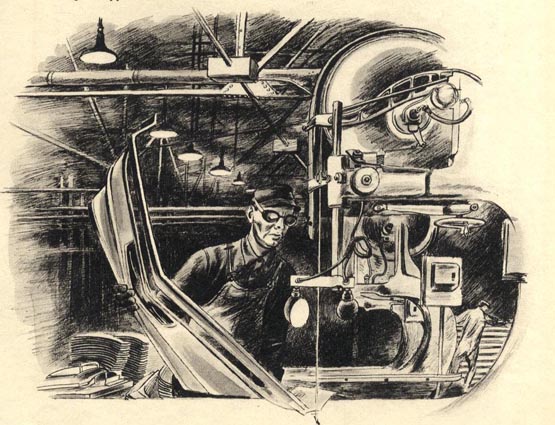

| BODIES BY FISHER | |

| ALBERTA | |

| CHEVROLET |

| BOHROD AND THE MAGAZINES

I wanted to ask you about your work during the war, and what prompted you to take the position that you did with—I guess it was at first Life Magazine. Was that your first _____? AARON BOHROD: Well, the first part of that was the. . . Well, I had done some work for Life Magazine off and on, work that you might call commissioned work, where it was suggested I go here and relate to this thing, relate to the other thing. They somehow liked my work and were interested in it. And those were more innocent days; they hadn’t discovered the Warhols and all the stars that have glistened since then. And their viewpoint was that the artist should look at life and respond to it and work accordingly. And their heroes were Grant Wood and Tom Benton and my predecessor at the university, John Stuart Curry. They would produce their work over and over again, and I kind of was dragged along with that general tenor. SUE ANN KENDALL: Was there a particular person at Life Magazine whose orientation was in that direction? AARON BOHROD: Well. . . Yeah, I think Daniel Longwell was the inspiration for it all. And he had an art director, Margaret Varga, who was also working in and interested in that particular thing, and she was something of a painter herself. But Longwell came from Neoshia, Missouri. And he was a good friend of Tom Benton’s, who also lived there close by. And he conceived the notion of the artist being put to work, by him, in Life Magazine as one other arm of telling the story of America, you know. So that he had a lot of the artists involved there. I remember I did a painting of Idle Hour Park, or something, in Fort Benning, Georgia, the roughest part of the world, almost you know, with the beatings and murders and so on. It was near a camp and that was their recreation of the boys, you know, with the drums of war beginning the beat, you know, just before we got into it then before Pearl Harbor. And then later on when the war started and Russia was one of our allies, Life Magazine envisioned a trip for me into Russia, painting whatever I wanted to paint: the country, the military activity, whatever I could see. And that entailed such an extended period of negotiation, largely of course between the magazine and whoever it was in Russia that was talking to them, that they never could see it. So that when a gallery that I was with, the Associated American Artists, had gotten together with such people as George—I’ve forgotten his last name. A few public-spirited artists who had come out of the WPA schools had worked with the Associated American Artists, of which I was a member—you know, Wood, Curry and Benton were also members of that group. Now they’re a kind of print organization, different from the painting organization. Well, anyhow, they had gotten together and started what they called the War Art Units. We were in the war already, and artists were beginning to be sent out to these scenes of action to depict, in any way that they were familiar with, the activity of the war, in an effort to build up a collection of art which would eventually be an adjunct to the photographic materials that were being collected, and which would show the nation what the war looked like at least through the eyes of a certain number of painters, artists. SUE ANN KENDALL: Did they seek you out, or did you seek out. . .? AARON BOHROD: No, I was sought out, because I was known to the Associated American Artists group and so on. And I was sent to the South Pacific originally. In San Francisco, where we were waiting to be dispersed in several different directions, I met a whole bunch of artists who were going, like David [Freedenthal, Friedenthal], who did some wonderful work during the war, mainly in the European Theater later on. SUE ANN KENDALL: Um hmm. AARON BOHROD: And Henry Varnum Poor went up to Alaska and Edward Lanning was among that group. Cummings, William Cummings was there, and, oh, in my group Charlie Shannon, from the south, and Howard Cook was also part of my group that went to the. . . Our group was called the South Pacific, or the Southwest Pacific, which was New Guinea and Australia and my group was headquartered in New Caledonia, and we went up to Guadalcanal and places like that. And then there other groups that were in the European Theater, although things hadn’t, you know, been activated to that extent yet in the European Theater. And I did one spell of work there gathering materials, painting on the spot, and then developing something when I came back to Chicago. And then, while I was in the Pacific, the army dropped its interest in the program, due to some Michigan, I think, congressman—forgot his name—who discovered that these left-wing artists were being supported by the army to paint the war, to give us a distorted picture; I don’t know what he had in mind.

I did a whole series of cover designs for Time Magazine, which stemmed out of my connection, I guess, of the work I did for Life. But it really came from a sudden new thing, the still life thing. And at that time, Time covers were all [noodled] out very carefully. They used to have a wonderful old guy by the name of Baker, Ernest Hamlin Baker, something like that. He took an ordinary face and made little ripples out of it, but gave it a sense of form, which was in line with the journalistic aim of Time Magazine, that was _____ aim.

Oral history interview with Aaron Bohrod, 1984 Aug. 23, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

|

Aaron Bohrod on wartime location drawing

from LIFE magazine

back