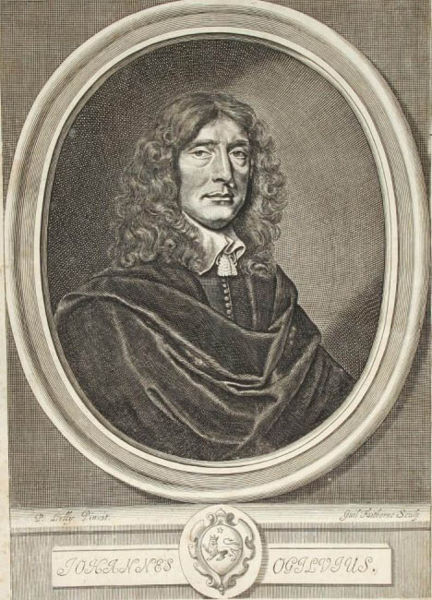

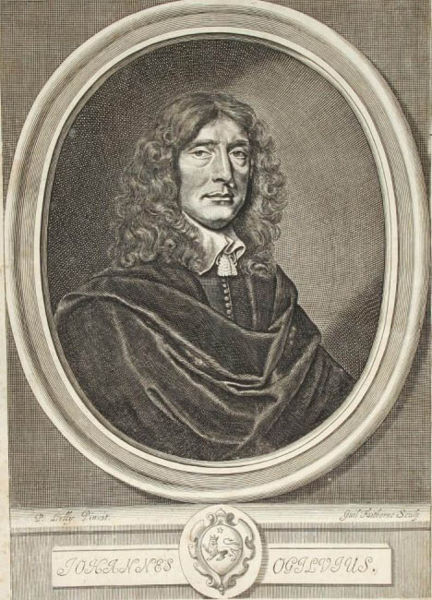

John Ogilby (1600-1676) was an enterprising Mapmaker and Entrepreneur. He had been a dancing master and choreographer until an accident left him with a limp for the rest of his life. Serving the Earl of Stafford as tutor to his children in Ireland, Ogilby then founded the successful Theatre Royal in Dublin. Losing his commercial fortunes in the Civil Wars, he reconfigured himself as a translator, learning Latin for the purpose of an edition of Virgil. The success of this enterprise was followed by translations from the Greek. His property was destroyed in the Great Fire of London, and he moved his activities to Whitefriars where he set up his business with a printing press, specialising in large and ambitious books, including splendid works of cartography. He was commissioned to produce three volumes of road maps but completed only one before his death in 1676, the most significant of the designated post roads in a pre-turnpike era. Each map measures 32 x 47 cms, not much bigger than the screen I am working on now. The whole volume was clearly not for the convenience of the traveller. A version of Ogilby was produced by John Senex in two volumes, Bowles, London 1757 that fitted the pocket rather than the Library shelf.

The first volume entailed, Ogilby claimed, surveying over 23,000 miles of highway, of which only a proportion of which were included in Britannia.Perhaps he can be seen on the titlepage (by Barlow) on horseback supervising the two surveyors with their Perambulator, exiting stage right.

The format he chooses for his Atlas is highly original, a system of scrolled parchment taking the reader from one destination, often London’s outskirts, to a designated town looking only straight ahead. Only once does a scroll (or at least the illusion of its unfurling,) received a variation – when the traveller to Aberistwith (plate 1) – takes a bifurcation to Oxford. The rules of reading are made very clear and sensible in the preamble. Each strip has an accompanying compass rose to register changes of orientation. The peripheral information is eccentric and often perverse – but always fascinating. The format was popular long after Ogilby, see the Great Western Booklet, Through the Window (Paddington to Penzance) 1924

The designer has supplemented the sheer sensibleness of the scheme with engaging little vignettes on each map, some abstracted cartouches, some scenes of mythological fun and games. On the road to Maidstone are Neptune and the Birth of Venus. Many of the more naturalistic vignettes show pictures of rural husbandry and the hunting scenes announced on the titlepage. Another graphic game that varies the monotony is the treatment of the scrolls, the neat terminations, or some chaotic rumplings. The illusionistic shading means that several worthy hamlets are condemned to a permanent state of the Penumbrum.

I hope the plates give some idea of Ogilby's art and industry. They are taken from a facsimile dated 1939 to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of the firm Alexander Duckham & Co, the blender of oils (now absorbed by British Petroleum) and suppliers of fuel to garages. They were responsible for several interesting maps, sometimes as gifts for customers. The copy used was from Duckham's own collection.

In 1686 the War Office in London commissioned a survey of the facilities for stabling and accommodation offered by inns and alehouses, adding further to the dense and fascinating information Ogilby had distilled into Britannia. There are several published account of travelling as dxescriptions in words. Ogilby demonstrated how much data can be displayed, even on a linear strip, of object and proximity.

|