|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

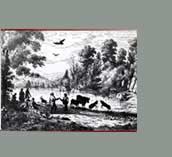

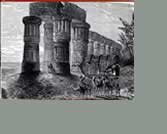

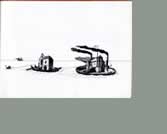

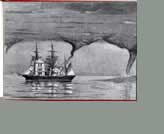

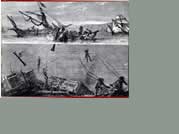

Anne Margaret Rutherford 1932 - 2006, born in Australia trained initially as a sculptor then at the Slade in London. She originally supported herself by mending antiques, and in particular tin toys and screens. The AIGA chose her first book, The Beautiful Island as one if fifty best books of 1970. Later illustrative campaigns were more commercial and conventional. Originally I presented a representative selection of the pages but the narrative became confused so I risk showing the totality of the book. The spread of the pages reveals a great care in pacing open and closed compositions, dark and light, flowing from left to right in a sort of Visit for Deserving Piles to the Isle of Cythera. At all times the Buildings maintain their architectural dignity. I can think of several illustrators who would leap at the opportunity of showing drip mouldings as eyebrows, and open doorways as expressions of horror. All the more effective when they find contentment on the Island, embedded on cliff faces or in cool caverns. The great lumps trundle around, are dragged and tipped over the cliff edge with a welcome absence of anthropomorphism. Her images allow the reader that great game - spot the addition to the basic picture. I suspect the presence of birds, vital to the liberation of the buildings may be a visually unifying factor in the individual scenes, glued on here and there to enhance consistency. The overall effect is one of an imaginative coherence driven by the very nature of the selection and juxtaposing of the original material, the wealth of nineteenth century wood engravings, once available for shillings in book shops. In the Illustrated London News and equivalents in Germany and France, there are regular features on the Architecture of the Picturesque, the Pitted Town Square facades often by old Sam Prout that specialist in the Dilapidated (Normandy and Brittany a favourite). There are regular full page features in the illustrated magazines on wild landscapes and stormy seas. Meg Rutherford simply forms her narrative from fusing one with the other. With only one exception, human figures are restricted to simple tasks of haulage in the compositions at the end of her drawn hawsers. There is no straining after increasingly garish effects, but a stolid and solemn building to a conclusion. She adds her own lines and shadows that reinforce the siting of the building in the landscape where the perspective systems might conflict. Hence the location is believable and sustained in a delightful and ingenious way. The writing is appropriately spare and confident and adds to my schtick the notable phrase, "nooks for the shy" which I intend to present shamelessly as my own conceit from now on. |