BACK

DR FRANK JACKSON, 59A, PRINCES ROAD, BRIGHTON, EAST SUSSEX BN2 3RH

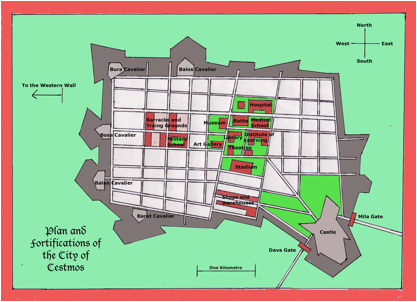

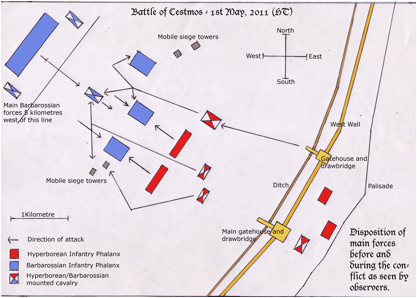

The Battle for the West The Brotherhood of the Hand, a small society, dedicated to mystery, consists of four elderly men, in equally elderly grey suits, who correspond to the fingers of the human hand. Simon and Annie, brother and sister, have become members of the Brotherhood, as have their friends, Indira, Pei-Ying and Mariko. There is also Adrian the seagull and Sniffer the dog, the eyes and nose of the Brotherhood, Sister Teresa a dedicated nun with strange powers, and Pat, an Irish academic. A new member is Morag, half-policewoman, half-faery. Together, they fight a war against their arch-enemy, Doctor Wrist, and his associates. During a journey to Hyperborea, the land of the faeries, they have succeeded in destroying one of the hated and murderous Wrist family. Having returned to Hyperborea, to aid their faery allies, they are on their way to prevent a war that has broken out against their western enemies, the Barbarrossi. They are about to arrive at the faery city of Cestmos, where the conflict has already begun. *************** It was a long ride to Cestmos. Ragimund had told them that, even with fresh horses, it would take all that day, and the next, to arrive at dusk. The news had not been good. Her face, after she had received messages that morning, had revealed its own story. ’There has been more fighting’. She told them, sombrely. ’There are more casualties. The Barbarossi have now brought up their main army, and are preparing for a great onslaught. We must hurry’. And so they had ridden out of Mila at dawn, subdued and quiet, across the second great bridge they had noticed yesterday, under and along the covered road, hearing the footsteps of people and guards on the arched walkway above. They turned right, listening to the soft chug of the river, and past the riverside kiosks, dim and quiet in the early morning mist, before turning again onto the road that led out to Cestmos. Their small retinue had grouped instinctively around Annie as they followed the wide stone road out into the countryside, protective, because of what she had told them last night on their return from their meeting with the griffins. They had rushed in anxiously, expecting Annie to have succumbed to horror and madness after her vision with the mime faery. Simon threw open the bedroom door, to find her, sitting placidly at the table, finishing a letter to her love, Helios. She looked up. ‘Is there anything wrong?’ she asked, mildly. Simon just threw his arms around her in relief. So did Mariko, both of them dreading that she had momentarily remembered the vision of hell itself that she had seen, but now, thankfully, could not remember. But she did tell them of Thursday’s gentleness, and that he had revealed that he was a student of their great friend and mentor, the alchemist Nicolas Flamel, whom they had last seen in Malta. ‘So Doctor Flamel is still keeping an eye on us, is he?’ said Simon. ‘I’m glad he is, bless him!’ ‘But Thursday is still a mystery’. Admitted Annie. ‘There was a lot that he didn’t reveal’. ‘But old Sawbones was good to you, and that’s what matters’. said Indira, practically. ‘He is a healer, and a physician!’ snapped Pei-Ying, suddenly and unexpectedly. ‘I’m Chinese, and I trust him!’ ‘So do I’. Replied Mariko. ‘I think he is a good man, but he has kept many secrets to himself. But we will find out sooner or later’. With that, they had to be content. Later, over supper, Ragimund began to tell them more about Cestmos, the fourth faery city they were about to see. ‘Cestmos is very different. It is a fortified city, with a castle. It houses our troops, and trains them for battle. There are barracks for our soldiers, and practice grounds for fighting. It is an enclosed city, with great fortifications. Like Dava to the south, which has also seen some attacks, it is an assembly point for our forces. You will see when we arrive there. It also has a great hospital for those wounded and injured. But it is under threat. We are sending them, as best we can, back to Mila to recover’. She paused, sadly. ‘We might encounter them on our way’. ‘What about the griffins? The two we met, are they the leaders? I can’t remember their names exactly, but they can surely do serious damage to these Barbarossi?’ Indira asked excitedly. ‘They can, but there are too few of them. They carry our soldiers to spy and observe, and occasionally attack, but they act as our eyes in the sky above. They have no liking for the Barbarossi!’ Ragimund almost spat the last words out. Annie sighed. ‘What about the dragons?’ Ragimund was silent for a moment. ‘They have sent a small contingent. That is all they can do. You should know that they are fighting a war of their own. The deposed dragon emperor has mounted a rebellion. Dabar is fighting for his own kingdom. He cannot come to aid us at present. So, It is just the faerys, a few griffins, and you’. Annie gasped, thinking of Dabar’s mate, her dragon-sister, Leila. On that note, the meeting had ended. Annie thought about it, as they rode on, and she turned her head to see Thursday behind them, in his small chariot, balancing himself on the interwoven leather straps of the floor beneath. He smiled and waved. Beside him was the faery Regina, who looked so like Rosamund, who had died at that battle long ago on the beaches in Brighton, in their own world. Her face bore no expression. Annie felt another twinge of unease. The faery had done nothing wrong. Perhaps it was simply her own anxiety. As they passed by, the horses trotting impatiently, hoofs clattering on the stone road, they noticed the country around them. There were fields and farms to their left, dotted with those small villa-farms and outhouses that they had become accustomed to. They were surrounded by the deep green squares of vineyards, and orchards of fig and olive-trees, tangy and sweet-smelling in the small breeze that had sprung up. Riding on, along the wide white road, great fields of wheat opened up, soft and flowing like water beneath the wind, sharp yellow, musty as earth under the bright blue sky. On the other side, long, low, blue-green hills folded and ebbed, broken here and there with grey and brown outcrops and small ravines. Small dark dots appeared, grew large on the road, and disappeared again, as the oncoming horsemen passed by, heading back towards the city from which they had come. There was a distant clatter. Ragimund reined in, and held up her hand to stop and move aside. The horses, strangely quiet and less talkative, moved uneasily next to the ditch that ran alongside. As they halted, a thrum of wings sounded in the air high above. A formation of griffins swooped, banked and then sped westwards in an arrow formation, small black figures perched on their backs. Their great leathery wings thrust up and down rapidly in unison, as they disappeared. The clattering wagons came up alongside, and stopped. Ragimund leant over from her saddle and talked briefly to the young blond faery who led them. He spread his hands, tiredly. His armour was battered and dented, and his tunic beneath was filthy with grey dust. There were other faeries sitting or lying in the open wagon, all of them bandaged. Brown bloodstains showed on the white linen. A very young blond faery stared back at Annie. His face was pale and dirt-smeared, and his eyes were dull and tired. He looked at Annie without recognition, exhausted and weary. The only sound came from a dark-haired faery girl who lay behind him, her leg heavily bandaged, sobbing quietly to herself. The faery leader gestured, and the wagons moved on, back to Mila. The last wagon was covered with a black canopy, but as it passed, Annie could see, with a jolt of horror, booted feet, that jerked slightly as the wagon moved on. The faerys were bringing home their dead. Thursday turned and watched them go, before shrugging his shoulders and flicking the reins forward. His face was grim. They stayed that night at a caravanserai, a stopping place for travellers and their horses. It looked like a great honey-coloured stone ruin, bright against the green hills beyond. As they rode through the entrance arch, they found themselves in a huge courtyard, with stables along one side, with rows of small doors and dormitories on their left and behind. Straight ahead was a long covered arcade set out with large tables and benches around which faeries, in armour, swords slung across their backs, sat and lounged, eating their evening meal. They dismounted, their horses immediately making for the large circular pool in the centre, lapping greedily at the fresh water. The faeries greeted them politely, but there was little pleasure in the air. Ragimund walked around the tables, greeting those that she knew, and talking quietly with them. They could almost feel the apprehension around them, as they ate and drank, and they were glad to get outside, and sit around the edges of the central pool, in the glow of the evening sun. A few minutes later, Ragimund walked across to join them. She sat down next to Simon, and absently dabbled her fingers in the water. They knew from her face, that something was very wrong. She looked around at them sadly, her face tired and older. ‘There is going to be a great battle. Not tomorrow perhaps, but almost certainly the day after. They told me’. She gestured at the faerys sitting silently around the tables. ‘You mean we’re too late!’ Annie gasped in horror. ‘All this way, and we’re too late?’ ‘Events have happened too quickly. There is nothing any of us can do to prevent it. They have moved a large force up, with siege-towers. The Barbarossi are about to attack our wall and try to breach our defences’. She looked miserably down at the surface of the water, rippling gently in the warm breeze. ‘So there’s nothing we can do about it?’ asked Simon, quietly. ‘Perhaps there is. It will depend on whether we can hold them off, and inflict a defeat on them. It may be that there will be a chance after that to parley, and find a way to negotiate a truce of some kind’. She sighed. ‘Gloriana can tell you more. She has taken command there, where they are gathering, with Lucifera and Mercilla. But I have one piece of good news. Jezuban is in Cestmos, and she is looking forward to seeing you again’. ‘Jezuban!’ Annie cried delightedly, thinking of that poor young faery who Simon and she had rescued long ago, and who had helped to save her brother’s life, after his encounter with the late Grandfather Wrist. ‘Is Duessa’s daughter well? Is she getting better?’ asked Simon, not quite knowing what Ragimund’s reaction would be to hearing her banished sister’s name. Ragimund’s eyes flickered into hard grey for a moment, then she nodded. ‘She is improving’. She looked at the others, who were bewildered. ‘You will see, when we get to Cestmos’. There was little else to say. Even Indira was subdued and worried. They slept in some of the little whitewashed cubicles along the wall of the caravanserai, though Annie still lay awake, listening to the voices of the faerys close by. They talked of training and exercises, and the prospect of battle. They were nervous and a little frightened, and she could overhear enough to understand that most, if not all, had never been in a war before. She slept at last. The next day was even harder than the first. Night was beginning to fall, by the time they reached the city of Cestmos. They rode under a gigantic overhanging cliff, that seemed as if it was about to fall and crush them under its weight. Annie caught a glimpse of lights high above, and could just make out the dim silhouette of a watch-tower. A mile or two ahead she could also distinguish a long narrow bulk, that seemed more forbidding as they approached. She realised it was Cestmos itself, though it was too dark to see. She felt she wanted to talk to someone, and leant down, close to her horse’s ear. ‘What’s your name?’ she asked gently. The horse lifted its head. It was desperately tired, but it answered politely, ‘Diglas’. ‘Are you worried about tomorrow?’ she asked gently. Diglas snuffled and snorted loudly in the silence, his ears twitching back and forth. ‘Yeah, I am. My brother’s a cavalry horse. He’ll be right in the thick of it. I hope he’ll come out OK’. ‘I’m sure he will’, replied Annie, trying to keep the anxiety out of her voice. They plodded on. The walls of Cestmos seemed to tower above them, as the road led them towards a wide entrance arch, encrusted with carved stone reliefs on each side. They depicted warriors in battle: worn as they were, they still seemed ferocious. But they were too tired to care. A cold chill emanated from the walls around them, with the damp odour of old stone. They rode into a courtyard, and dismounted, the horses led off gratefully to the stables. ‘Please come and see my sisters’, Ragimund said, and led them through a narrow archway into the castle. They climbed up stairs, and walked through endless stone corridors, until she stopped in front of a pair of double wooden doors, and walked in. They followed. Four figures rose up from a long table scattered with plans and diagrams. ‘Annie!’ shrieked a small female body. ‘Simon!’ Jezuban threw herself into their arms. ‘It is so wonderful to see you again!’ She let go of Annie and hurled herself into Simon’s arms, who staggered slightly from the impact. ‘Jezuban!’ he laughed delightedly, as he managed to disengage himself. ‘You speak our language now!’ ‘I have learnt! I know how to write it too!’ ‘Welcome, all of you’. said Gloriana, standing behind the table. She smiled, though Annie suddenly noticed that her face, though still beautiful, was drawn and tired. ‘Did you like our city of Mila?’ ‘Absolutely!’ cried Indira, excitedly, before anyone could stop her. ‘It was one of the most beautiful places I have ever seen’. Added Mariko, quietly. Gloriana’s sisters, Lucifera, and Mercilla, smiled back at her. They had not changed. Lucifera, the taller, had the stronger face, framed by her long brown curly hair. Mercilla’s still had the rounded softness of a young girl, her long blonde hair falling down almost to her waist. ‘Tomorrow’, said Gloriana, her voice sharper and brisker, ‘My sister Ragimund will take you to the western wall. I have arranged that you will be provided with armour, and you have your own weapons’. ‘Why?’ asked Annie, gently. ‘Because we are going to war’. replied Mercilla, sadly. ‘We have no choice. It has been forced upon us. The Barbarossi are already shifting their forces in readiness’. There was silence for a moment. ‘Is there nothing, anything we can do, to try to stop it?’ asked Simon, miserably. ‘No’. said Gloriana, flatly. ‘It is inevitable. But,’ she went on, looking around at each of them, ‘ I want you to be there, because we may have need of you. I will not permit you to take any part in what may happen tomorrow. You are our envoys, our negotiators. I do not know what the day may bring. My sister Ragimund, will command our walls. As for us, we go out to fight a war’. ‘We will cut them down like wheat before the wind!’ snapped Lucifera, viciously. Her eyes had turned a hard grey. Annie’s heart sank. She knew what that meant, and it chilled her. She stared down at the marble floor. ‘We will do what we can’. she said, and then turned and walked through the door. After a few moments, the others followed, leaving the three faerys to sit down again at the table. Their rooms were similar to those in Mila, and they sat and ate at the same kind of low table that Mariko liked. Jezuban chattered happily, but the others had no heart for conversation. The mood was sombre, and even Jezuban began to give up after a while, after she realised their unhappiness. Presently she excused herself and left. No-one felt like talking, even Indira, and presently they retired and went to bed. But Annie stayed awake for a while, and began to weep silently. Finally she cried herself to sleep. **************** The next morning was bright and clear. The windows in the tall panelled room were high and narrow. There was no balcony outside, or veranda. This was a castle room, hard and austere. The others were gathered, leaning on the sills, gazing out on the city of Cestmos. They moved aside as Annie joined them, and saw it for the first time. She gave a cry of surprise. It was a red city, a city built of hard red brick and mortar, unlike the marble and stone of Elsace and Mila. Cestmos was a place buttressed against war with sharp jutting fortifications, silhouetted against the distant flat country, surmounted by small square forts. In the centre of the city stood large towers, broken by projecting sharp eaves and roofs, that rose up storey by storey. The windows were tight and narrow, outlined by shadow. There was none of the austere elegance and dignity of Elsace, nor the exuberance and ascending beauty of Mila. This was a tough city, built to resist and fight, clear-cut and brutal. It was a citadel crouching like a lion, for battle. ‘Annie, you must eat something’. She turned, startled. It was Ragimund, who wore armour. Her long brown legs were bare, apart from long boots to just below her knees but she wore a polished breastplate and plated segments of steel, that overlapped her shoulders and upper arms. Pushed back over her head, was a full helmet, that Annie recognised as a Greek helmet, shaped and moulded, with slanted apertures for the eyes and a protective nose-piece that extended downwards. She had seen them in pictures in her childhood. ‘No thank you’, Annie replied miserably. ‘I’m not hungry, not today’. ‘I really fancy myself in that helmet!’ Indira giggled. ‘It suits you, Ragimund. I think I’ll look good in that. With my raven tresses’. ‘Oh, it will’. sniggered Pei-Ying. ‘Especially, if it hides your cheeky face!’ Indira stuck her tongue out impudently at her. Annie suddenly reached across and held Indira’s left hand. ‘Where’s your bandage?’ she demanded. ‘Don’t need it any more. Look!’ She held out her palm. There was no mark or scar. The soft skin had healed completely, but Annie pulled her hand over sharply. Between the index and middle finger, just below the knuckles, was a cruel white scar, highlighted by Indira’s warm olive skin. Indira looked down at it sadly. ‘I know. It’ll always be there as a reminder of my own stupidity’. Annie gently clasped her hand, over the scar. ‘Your loyalty and friendship’. She said, quietly, ‘And my own stupidity’. ‘We must go!’ Ragimund said, urgently. ‘My sisters are at the western wall now! They departed last night, preparing for the battle!’ They rode out, through the Dava gateway, past the heavy, sharply angled walls, that rose up ominously on their right, scarred stone, pockmarked with patches of green moss. Behind them, the castle of Cestmos stood high, sharp and angular, each level marked by a sharply curving roof, so like Chinese and Japanese forts. The angles of each roof rose aggressively into an upturned peak, the walls pitted in a symmetrical pattern, with dark narrow windows, slanted inwards to give the archers inside a better range and view. It was ruthless, even arrogant. Below the tall central keep, another wall ran around it, then another wall, savagely angled to repel any kind of attack. It was truly a vicious building. Annie turned away from it, her face downcast, as she thought of the day ahead. They rode through a long grassy plain, towards the ochre-coloured walls in the distance that snaked up and down, north and south. They could already see the black line of a palisade that ran behind it, and the massed white shapes of faery tents between that and the wall itself. From less than a mile away, they could hear the tumult of a faery army, the sound of the sea breaking on the shore. They entered through a gap in the palisade itself, guarded by armed faery soldiers, who nodded them on as they were recognised, and found themselves in the midst of a milling throng of faerys, gesturing and shouting loudly to others that they recognised, a bustle of activity that signalled the oncoming battle. There were a few wolf-whistles and bursts of laughter, as Indira painfully dismounted outside a large brick building just inside the west wall itself. She glared around furiously, at the faery soldiers who immediately pretended to look somewhere else. ‘This is our armoury’. Announced Ragimund, as she indicated the rows of shields, body armour and helmets that were arrayed on every wall. To their right, they could hear the hammering of anvils, and the roaring, whistling sound of a forge behind the wall. ‘This is our armourer, Vulcan’. ‘Vulcan!’ gasped Simon in surprise, particularly so when a small, wiry figure emerged. Unlike most faerys, he was not tall, and his arms, well-muscled, seemed overlong for his short body. He was bald, but his face, though lined, and with a sharp, hawk-like nose, was benevolent, his lips curving up into a kindly smile. Ragimund spoke to him rapidly in her faery language, and he nodded, his gaze most of all on Indira, who bristled defensively. He muttered something to Ragimund, who giggled, and then tried to look solemn. She whispered something to Simon, who immediately sniggered, then did his best to look serious. ‘What’s the matter?’ snarled Indira, angrily. ‘It’s very worrying, Indira’, Simon was trying desperately to keep his face straight. ‘But he says it will be difficult to find armour for you, because you have …..protuberances’. ‘What?’ ‘’I think it means, Indira’, said Annie, tactfully, forgetting her own dark mood for a few moments, ‘that you have what we might call, an ample bosom’. ‘Protuberances! I’ve never heard them called that before! I’m not that bad, am I?’ She turned to Pei-Ying, sadly. ‘Hardly. You heard them all whistling at you’. Indira soon cheered up after a while. With the help of two other women faeries, the armourer had provided them with the same kind of armour that Ragimund already wore. Annie stared at herself in the polished mirror in the corner of the armourer’s room. She looked hard and strong, the armour feeling light around her upper body and shoulders, flexing with her movements. She looked like a warrior, and just for a second, she wished herself back in school, a young girl at her lessons. The armourer handed her a helmet, like the Greek helmet that Ragimund wore so easily. He tapped it. ‘Steel’, he said, as if it was the most important thing in the world. Annie held it, looking at it as if it were her own face. It was cruel, sinister, with empty slanted spaces for her own eyes, and a long nose-guard. The bottom edges were curved outwards to protect her throat and neck. There was a cruel beauty to it, and it felt light, but immensely strong in her hands. The armourer indicated with his hands that she should try it on. His command of her language seeming to be non-existent. She put it on, and looked at herself. The helmet had slipped on easily, as if it had been moulded to shape her head. To her surprise, she found she could see well, both to the side and the front. She could still hear, through the perforations over her ears, though it was more muffled than usual. It was also comfortable to wear, the deep leather and lined padding inside cushioning her face and head. She pulled it off again, and held it in her hands. It was a skilled piece of polished and burnished craftsmanship, strong and wonderful, but it was still the hard, metallic face of war. She could imagine it, implacable and furious, on the battlefield. She shivered. They followed Ragimund up the narrow wooden stairs up onto the wall itself. Annie looked around. Each side of her were large stone gatehouses, around which, behind and below her, the faerys were massing. The wall was battlemented, and lay, about eight feet wide, paved, as far as she could see, to right and left in both directions, disappearing into the distance. She looked down over the walls, behind which faery archers were preparing their bows for action. Beneath was a long narrow ditch, brown and dry, that ran along the entire length of the wall, as far as she could see. And beyond the ditch, was a large flat plain, covered in flat green grass, scuffed and muddied by feet and hoofs. It rose and fell in small, slight slopes. It was the perfect place for a battle. ‘A killing ground’. Simon said softly, beside her. They stood together looking at the low hills that lay in the distance. Just below the hills, a great host were advancing, silvery, with the sun glinting from upraised spears. They were advancing slowly, very slowly, but in large formations. Tall structures, on each side, began to appear, moving slowly alongside the troops, marching in close formation. It would take some time for them to arrive, but there was no doubt that they were moving towards the faery wall. Annie could feel that terrible dread, the wait before a battle. She turned abruptly and went down the stairs to the open space below, where the faery warriors were already mustering. To one side stood a forest of spears, nearly sixteen feet long, their spiked butts planted firmly in the trodden earth. Each one had a bullet-shaped tip, designed for penetrating chain-mail, that gleamed wickedly in the bright sun above. Beside them were great piles of shields stacked together, curved, rectangular, painted with a great open eye, exactly the same as she had seen on the bows of the trireme, Narcissus. The faerys milled around, gossiping, talking loudly to each other, but she thought it was due to their desperate need to talk about anything, anything, to take their minds from the conflict ahead. She was astonished and saddened by how young they looked, even for faerys. Few of them were more than her own age. She suddenly caught sight of a tall, slender figure perched on one of the wooden benches in the shade beneath the great walls. Impulsively, she walked across. She wanted desperately to talk to one of them. She sat down next to the tall young faery girl, whose lips were trembling. She looked frightened and nervous. Her hands were clasping and unclasping in her lap. ‘What’s your name?’ asked Annie gently. The girl looked up, startled. ‘I’m Annie, by the way’. The girl gasped. ‘I know of you! You are one of those human warriors that have come to help us! I have heard such wonderful things about you! You have fought monsters and daemons! You have done great things!’ She automatically inched away from Annie, then she remembered. ‘Oh, please! Forgive me. My name is Vela. I am fighting in the First Phalanx, Second Row’. Annie looked at her carefully. She seemed very young, tall but with that awkward lankiness of someone who had only just grown up. Her dark hair was cut to neck-length, clustering in curls around her pretty face, that still had the soft roundness of a child. ‘How old are you. Vela?’ Annie asked gently. She felt like an old veteran against this girl. ‘I am forty-eight years old on my next birthday’. replied Vela proudly. Annie made a swift calculation in her head. With a stab of horror, she suddenly realised that this girl was only fourteen years old! Vela must have seen it in her face. ‘I know I am young’, she said hesitantly. ‘But I volunteered. I was the best in my class in tactics and strategy. How old were you when you fought your very first battle, Annie?’ she added eagerly. ‘The same age as you’. Annie replied sadly. She paused. ‘Are you frightened, Vela?’ ‘No! I’m….’ she looked down miserably. ‘Yes. I am very frightened’. Annie looked at her with a desperate compassion. Then she thought of something. She began to rummage down into her small satchel bag that she always carried. Vela looked puzzled. Then Annie found it. ‘Is that your helmet?’ she asked. ‘Yes’. She passed it over. Annie held it in her lap for a moment, cradling it almost as if were a child. Then she began to scribble on the side of it, with the blue marker pen that she always seemed to carry around with her. Just for emergencies. It was a kind of sketch, of an outstretched hand, palm outwards in a gesture of peace. After a moment’s thought, she carefully enclosed it in a pentagram, remembering, as Simon had shown her, to draw it without lifting her pen from the smooth surface of the helmet. She handed it back to Vela, who looked at it in amazement. It’s not very good, I’m afraid’, Annie said sadly, ‘But that’s the emblem of the Brotherhood…and Sisterhood…. of the Hand. I hope it will bring you luck…..and hope’. Vela stared at it, her brown eyes alive with excitement and delight. ‘This is the sign, of your warrior society? Is it a talisman?’ ‘Well, sort of’, said Annie even more sadly, thinking of what her “warrior society” consisted of, including a sexist seagull and a smelly dog. ‘I hope it helps you, and your comrades’. ‘It will! I will tell them!’ she looked at Annie in gratitude. ‘Thank you so much….Annie. It will give me courage!’ The sudden sound of a strident horn rang out. Immediately the faerys began moving, pulling their shields from their piles, and yanking their tall upright spears from the ground. They began to mass together in formations, now cold and purposeful. ‘I must go to join my formation!’ Vela stood up and then hesitated. ‘Will I see you again?’ she asked in the small, lost voice of a child. ‘I’ll be here’, Annie smiled, though she did not feel it. Then she pulled the young girl towards her, and kissed her gently on the cheek. ‘Please come back safely, Vela’. ‘I will’. She smiled shyly, and then, holding her helmet, that Annie had made so precious, she turned and ran towards the phalanx of faerys that were already forming. The hubbub of noise grew louder, as the faerys began to arm themselves, snatching spears and shields. The small armourer was trotting around them, urgently supervising and adjusting equipment at the last moment. The tension had gone: this was now the frantic hurried surge of soldiers preparing for battle. She caught sight of Vela, talking excitedly to her companions. She saw Annie and waved. She waved back miserably, turned and went back up the wooden stairs to the battlements, her heart weighing her down, as heavy as a lead weight in her chest. ‘Where have you been?’ demanded Simon, as she stood by him on the walls. ‘Look!’ He pointed down at the plain in front of them. She saw with horror, the two great phalanxes of the Barbarossi moving purposefully towards them, their large circular crimson shields forming a wall as they marched, their spears held upright. There were two, with another on the right, but much further behind. They were moving slowly and clumsily, it seemed to Annie, even with her untrained military mind. The large siege towers, two on each side of the phalanxes, were rumbling forwards, propelled by smaller groups of troops behind. Barbarossi cavalry, behind the middle phalanx, were hovering, horses stamping and wheeling. There was a great crash as the drawbridge of the gatehouse to the left of where they were standing came down, across the ditch. The faerys began to march out, forming up into their own phalanx. It was swift and precise. No sooner had the first phalanx formed, then another appeared, mustering into another. They were gathered in two formations, wide but with eight soldiers deep. Their long spears, held upright, bristled like a sapling forest. Then they began to move, walking towards the enemy, with a deadly purpose. Behind them rode out two large groups of horsemen and women, all armed with smaller but lighter spears and bows, slung across their backs. She looked northwards along the wall to the other gatehouse. There was a huge mass of horses and riders gathering behind, milling and whirling furiously. She saw Gloriana, Lucifera and Mercilla mounting their horses, then taking their own helmets from the faery soldiers below. She realised they were about to emerge from the gatehouse into a charge. It was the dreadful moment before a battle set into its inexorable course, whatever the outcome might be. Ragimund crouched down next to them, as they peered through the gap in the battlemented walls, at the plain stretching before them. ‘I do not understand it!’ she whispered, in that dreadful quiet lull before a battle was about to begin. ‘They have left their siege-towers isolated, and their left flank exposed! Their main force is more than four miles away! If we break their attack, they are lost! It is just madness! Their cavalry is too far behind to have any effect! What stupidity is this?’ ‘Or deliberate’. Simon said, quietly. ‘I don’t know that much about war, but why aren’t the siege-towers in front of their phalanxes, to break up an attack?’ ‘My sisters will fall upon them and slaughter them!’ Ragimund stood up angrily. ‘This is not the way of a warrior!’ She strode off angrily, to supervise her own troops manning the wall. Annie looked at her brother. ‘Is that true, Simon?’ ‘Yes. It’s stupid! Even I can see that! It’s going to be slaughter, Annie! But we can’t stop it now!’ She could hear the despair in his voice. She looked back at the two forces now closing for battle on that great plain below. She thought of Vela, and prayed quietly to herself that she would survive. **************

Their commander in the front rank shouted. Instantly, the faerys in the First Phalanx stepped up their pace, their feet in perfect unison, the pounding of their boots on the trodden earth creating a powerful rhythm. Vela’s heart too, was pounding as she marched onwards, her comrades beside her and in front. Her hands were wet and sweaty around the shaft of her spear, that she held upright, as the others. Their shields bumped against each other, reassuringly, as they moved steadily towards the Barbarossi, their circular red shields looming larger and large before her eyes. Their helmets were pulled down, and all she could see now were the backs of her comrades, and beyond, the enemy. But she could feel the press of her comrades around her and behind her. Now her world was enclosed inside her helmet. She could feel and smell the sweat, and hear the small clatters of sound, the slight rattle of armour, moving with bodies, in the tight enclosed space around her. The steady pounding of their feet was the only sound that she was conscious of. But another pounding, a faster furious rhythm suddenly sounded in her ears, in her helmet. Panic and terror suddenly rose up in her throat, forcing her to gag, and cry out, though no-one around her heard. She remembered the talisman on the side of her stifling helmet, the one that that lovely human….Annie?... had drawn on it. Her courage returned, and with it, her anger against the enemy. She gripped her spear harder, feeling the weight of her sword on her back. The pounding outside now was stronger, but it was behind her. With a shock of relief, she realised that it was faery horsemen, coming to support them. Now her faery bloodlust began to descend, as it did on those around her. ************** The faery horses roared out of the north gatehouse in a torrent of maddened fury, their riders crouching low with short spears glistening. They tore like an unleashed river towards the enemy, the glistening arrow tips of those deadly spears straight towards the central and left phalanxes of the Barbarossi, already closing with the faery phalanxes, that were moving faster and faster towards them. More horses and riders poured out of the main gatehouse to their right, armed with the deadly composite bows that Annie saw the faery soldiers were holding taut on the battlements each side of her. One group was heading for the space between the faery phalanxes now moving swiftly forwards to hit their enemy. The other swung to the left, to attack the siege-towers rolling towards the walls. Annie felt sick with horror, as she watched the scene below. Though she had not at first recognised them, she had seen Gloriana, Mercilla and Lucifera. They rode at the head of the great river of horsemen that now poured towards the Barbarossi, Gloriana wearing an armoured mask of a devil, its face set in a fury of hatred, mouth downturned, its coarse black hair streaming behind it, Mercilla, the bland bronzed face of a Roman leader, and Lucifera, the hooded and beaked face of an eagle. They were bearing down on the enemy on their pommelled saddles, not even holding the reins of their horses, caparisoned in robe-like armour, and faceguards, their riders gripping a long curved sword in their right hand and a short stabbing spear in their left. They were terrifying, as they galloped at the head of the vicious storm of riders towards the enemy, already beginning to falter. From the walls behind, the impact was only seconds away. ************* Vela was panting, her senses heightened, the impact with the enemy only moments away. The leader in the front shouted. His voice sounded hoarse. The spears came down heavily, their tips gleaming viciously. She lowered her spear down to rest on the notch of the faery’s shield in front of her, changing grip, so that she held it overarm. She felt the soft thrust of the spear behind her as it slid across her right shoulder. Then another, as it slid across her left, catching slightly on her helmet as it pushed forwards. The leader shouted, his voice suddenly louder, then they broke into a savage run, keeping their perfect formation, as they had been trained to do. Their shoulders were now hunched, ready for the impact. The bloodlust filled them with faery fury, as they stormed down the slight slope towards the enemy, now huge, alive, braced to meet them. The young Barbarossi panted, breathing heavily. Then he looked up. He saw the faerys coming down on him. He saw the great eyes on their shields, and he heard their terrible war-cry as they charged down. He saw that array of spears glittering, pointing straight at him, in the late afternoon sunlight. They came down like an avalanche, smashing into his phalanx like avenging angels. He saw the dark brown eyes of a young faery, her eyes blazing, and then he was swept away. *************

Annie could feel the heavy impact as the two faery phalanxes smashed into the Barbarossi, whose ranks crumpled under that massive fury. They began to collapse upon themselves, those in front crushed against their own comrades behind. Unable to use their spears, they had to fight to retreat backwards, where they might stand, be capable of using their weapons. But the faery riders gave them no chance. They charged into their unprotected backs, thrusting savagely with their spears, as they split in three directions. Gloriana tore ferociously into the back of the smashed enemy phalanx in the centre, hacking ruthlessly down into bone and flesh, her sword flashing as it rose and fell in great sweeps. Mercilla swerved, and led her horses into the back of the unprotected phalanx on the right, breaking into their formation, forcing them to stagger and desperately try to turn to meet the attack. Lucifera turned her troops savagely into the defenceless flank of the mounted Barbarossi, shifting uncertainly in their saddles as they saw her vicious beak-like mask. Armoured as they were with chain-mail, conical armed helmets, only their eyes left visible, they turned desperately, caught by the speed and ferocity of the attack. It was too late. Their horses were thrown down by the impact, and their riders rolled on the ground, too winded and bewildered to try to avert the spears that came down upon them with the wings of death. ************** The griffin soared above the battleground, its great leathery wings outstretched as it caught the upward winds. It could almost feel the heat of the battle beneath. The rider, a young faery, looked downwards. She could see the swirling mass of riders and the enemy phalanxes broken from front and behind, shattered and scattering. Small groups gathered to try to fight their way out, only to be slashed down by the riders’ whistling blades. The griffin glanced down. ‘Massacre’ it grunted in its harsh clacking tone. ’Keep out of arrowshot!’ the faery warned as she looked down again at the carnage below. ‘This is not our way!’ she cried, furiously. The griffin only grunted again as he continued to circle slowly above. ************** Vela felt her spear almost hurled back as they struck the Barbarossi, its shaft jolting and juddering in her hand. She thrust again and again at what was in front of her. She was almost blind with rage, the bloodlust flashing before her eyes. She screamed in a mixture of terror and fury, though only she could hear it. Her spear twisted as it drove into something, and the shaft snapped suddenly. She and all those around her, could feel the enemy suddenly give way, and break. She heard her leader shout furiously, and they surged forwards again, their shields edge to edge, as they smashed further into the Barbarossi formation. Their leader shouted again, his voice sounding far away in her helmet. The enemy had broken, and were desperately retreating backwards. The leader shouted again, and this time she understood, and dropped the broken shaft of her spear, and drew out her sword instead. They all moved instinctively apart, to give space, as they hurled themselves towards the broken groups of the enemy before them. ************** Annie felt sick with horror as she saw the broken remnants of the Barbarossi forces, scattering and running desperately before the faery phalanxes as they surged onwards. She saw a Barbarossi, impaled on the spear of a faery horseman, wriggling like a fish. She saw another transfixed against the wall of one of the siege towers, as the faery archers, drawing and firing their bows with unbelievable speed and accuracy, picked off the fleeing enemy. The faery horsemen rode here and there, their horses smashing and trampling down with their hoofs everything that stood in their way. And still the slaughter continued, as the faerys, relentlessly, and savagely, cut down the retreating survivors. She saw the two siege-towers on her left, burning furiously, as the faery horsemen hurled small incendiary pots or vessels into them. The dry wood on the inside had caught instantly. Small figures, alight with fire, fell like flaming matches to the ground below. The other towers on the right, stood abandoned, as the soldiers manning them scurried like black ants towards the distant haven of the hills behind. She watched as the faerys, those mounted and those on foot, finally halted and began to retreat back towards the gatehouses on each side of her, leaving behind a field of death and destruction: the wounded, and the dying intermingled with their dead, their moans and cries carried towards her softly by the wind. Below, she could hear the heavy tramping of boots on the drawbridges, clattering and creaking under the weight of the faerys gradually streaming back through the wall on which she was standing. The noise of their voices, both hushed and excited, reverberated along the stone battlements, as did the steady thud of the horses as they filed through the portal of the other gatehouse, and met with their comrades who had stood in reserve on the ground in front of the wooden palisade. She could hear no sound of jubilation, or celebration, just the sound of their voices, rising and falling, as they talked quietly of the battle they had just fought. Annie slid down against the hard stone wall, her hands clasped around her knees, the rasp of her armour loud against its rough surface. She pressed her cheek against it and began to weep, uncontrollably, her tears trickling down her face. She wept for all the poor soldiers that had died, people that she didn’t even know. She wept for those she had cared for, the plump little figure of Mr Cuttle, who had gone into battle with them, armed only with an umbrella, the small dragon whose body had gently rolled in the waves, the red-haired girl in the photograph from so many years ago, and whose eyes she had closed, as she lay dead, the young girl, Annabelle, young and trusting, who had been cruelly beaten and murdered, a hundred years in the past, and even for Venoma, who had been borne away in the dark sewers of Brighton. She cried and cried, her hands pressing against the stone, the talisman on her hand glowing softly. ************** She did not know how long she had being there, but suddenly her brother was beside her, pulling her shoulders urgently. ‘Annie! Annie!. She stood up and clung to Simon. He held onto her tightly, two young children clasped together. ‘I thought I’d lost you again!’ ‘Again? I suppose so. I’m sorry, Simon’. She wiped her face with the back of her hand. ‘I’ve been crying’. ‘I know you have’. Simon said gently. ‘That’s why I came to find you. Your’e a horrible little sister, but for some reason I rather care for you’. ‘I’m not your little sister!’ Then she softened as she saw his anxious face. ‘Thank you, Simon. I’d just had enough’. ‘I know. So have I!’ he said bitterly. ‘All the faerys are back now. At least, most of them. Some of them got killed’ Annie’s eyes widened with horror. ‘I must find Vela!’ ‘Who?’ ‘Just stay here, Simon! I must find her!’ She turned and clattered down the wooden steps to the open space behind the western wall. It was crowded with faerys who stood in groups, talking and chattering, anything to keep themselves from remembering the battle they had just gone through. She looked around frantically. ‘Vela!’ she shouted. ‘Vela! Where are you!’ She shouted again, her voice now desperate. ‘Vela!’ ‘She is over there, lady’. It was a young dark-haired male faery. ‘I was in the same phalanx with her’. He said quietly. He pointed. There was her tall slender young figure, sitting on the same wooden bench, her helmet beside her, in exactly the same position as when Annie had first met her. She ran towards her, pushing past the huddled groups around her, who stood aside politely as she struggled towards the young faery. Vela was staring ahead of her, her eyes shocked and vacant. Annie looked at her helmet beside her. It was spattered with wet blood, smeared across the little talisman that she had drawn on it. ‘Vela!’ She fell down on the bench beside her. For a moment, Vela looked at her without recognition, and then her eyes widened. ‘Annie!’ she cried, and flung her slender arms around her, clinging as a terrified child would to a mother, as Annie had held onto Simon only a few minutes before. After a few seconds, Annie very gently pushed her back, and looked at her. Vela was sweat-stained, her face dirty with dust. She looked back at Annie. ‘It was very terrible, the battle’. She said miserably. ‘I was so frightened! So were my friends. But they were there for me! I fell over somebody’s body, and my friend protected me! He held his shield over me, as I got up!’ She began to gabble in shock, then looked down. She burst into tears. Annie looked down as well. ‘Vela. Don’t worry. It happens to anyone.’ ‘I feel so ashamed!’ ‘You mustn’t. Hold my hand., Vela, and I’ll take you to the latrines and help you clean yourself up. Come on’. She quietly led the still sobbing young faery through the noisy mob of the others, who parted immediately, to let them through. A few minutes later, they came back and sat down on the bench together. Vela looked down again shyly. ‘Have you ever been .….afraid…in battle…..I mean…Annie?’ ‘Yes. I’ve always been afraid’. Annie replied, quietly. ‘Annie, may I ask you something?’ Vela said, very timidly. ‘Of course you can’. Annie looked at her. She seemed better, though she was still trembling slightly. ‘Perhaps….perhaps you would come to see me again and meet my mother and father, and my little brother and sister? I..I would so much like you to. Your brother too, and your friends. It would be so wonderful if you could!’ Anie looked again at the young, rather ungainly faery, and felt a tremendous affection for her. ‘I will, when I can. Where do your family live?’ ‘In Rhuan. Oh, Annie, it is such a wonderful city! Have you been there?’ ‘No, I haven’t. But I would like to. I must go, now, and you should join your comrades’. ‘Yes, I must’. They both stood up, though Vela hesitated. ‘Will I really see you again, Annie? You have been so good and kind to me’. She picked up her bloodstained helmet, and looked at Annie with wide appealing eyes. ‘Will you be my friend, Annie? I have my comrades, but I don’t have any close friends. Do you?’ ‘Yes, I have. True friends that I value very much. But I will be your friend, Vela, if I can. I think you are lonely, but you are also very brave too’. They hugged each other hard, and then Vela went quietly to join her comrades, waving to Annie as she left. Annie looked after her, and then turned, and walked sadly up the wooden stairs to the battlements. But there was worse to come on this wretched day. ************ She looked out across the battlements of the wall. The dead Barbarossi lay like fallen autumn leaves across the plain, their bodies strewn, in places more than two deep, their limbs outstretched like fallen branches, and their dead faces wearing the same surprised mask of death, their conical helmets scattered around. But Annie couldn’t weep any more. She was too worn out and tired. Behind her a loud horn rang out in the fading day. She looked around. A tall faery, a few yards away, noticed, and came over to her. ‘Here, lady, you must be thirsty. He offered her a flask. She gulped the cold sweet water it contained. ‘Thank you’, she said gratefully. ‘What was that horn for?’ The faery stood up and looked out over the battlefield. ‘It is a signal that they can come and collect their dead, my lady, as we will our own. It is a short truce’. He stared out again over the sight before him. ‘This is not our way, my lady. Once we had broken them in battle, we should have let them flee. To slaughter them like that is not right!’ He spoke so vehemently that Annie was startled. She handed the flask back to him. ‘I’m not lady, just Annie. Just call me Annie’. The faery smiled, sadly. ‘My name is Pereas. If you need anything, call my name’. He turned around and went back to his post, picking up his vicious-looking bow. Annie leant against the wall, and looked miserably at the terrible carnage the faerys had wreaked. There was a sharp thud of boots on the wooden stairs behind her. Gloriana, her mask flung back on her helmet, walked up, followed by Lucifera, her eagle mask also swept back, and Mercilla, who still wore that same bronzed still face, that she had noticed earlier. They looked out over the wall, their backs towards her. They began to talk briefly, but as their conversation began, Annie heard more loud footsteps behind her. She looked around. It was Ragimund, her lovely face contorted in fury. Her hands were clenched at each side. ‘HOW LONG WILL THIS SLAUGHTER CONTINUE!’ She screamed at the three figures. ‘Answer me!’ The three figures ignored her. ‘I am a faery! I am a warrior! I am not a butcher!’ The three figures turned and began to walk down the wooden stairs, without a single word. Ragimund stared after them, tears beginning to run down her cheeks. ‘They did not look at me! They did not even look at me!’ she cried. She tore her helmet from her head and hurled it after them. It bounced, clattering and banging along the battlement until it came to rest against the wall, dented and scratched. The faerys crouched along the wall, looked at it nervously. Ragimund was now crying bitterly, just as Annie had done earlier. ‘I hate you!’ she screamed after her departing sisters. ‘You are not my sisters any more!’ She turned and stormed away down the stone path of the wall towards the far gatehouse. Annie desperately tried to catch her arm, but Ragimund shook it off. ‘Leave me! Leave me alone!’ Annie stood and watched her, transfixed with horror and dismay. Suddenly, everything fell into place. She had to do something, anything to stop what was happening. Her brother came, stomping up the stairs, stopped and stared at his sister. ‘What’s going on?’ he demanded. ‘I heard Ragimund shouting, and then those three just went past me without a glance!’ Annie grabbed him by the arms, pulling him hard so that he looked directly into her face. ‘Do you love Ragimund? Do you love her?’ She shook him by his arms. ‘Tell me, Simon! Tell me truthfully!’ He looked at her in sudden alarm, at her frantic face. ‘Annie, don’t go away from us again! I can’t bear it!’ ‘Do you love her?’ Annie cried. ‘Do you?’ ‘You know I do! You’ve always known! I love her so much!’ he shouted, desperately. But Annie still held on tightly to his arms. ‘Then tell her, please. Simon! You must, for her sake, and yours! I’m afraid for her!’ ‘What do you mean?’ he cried wildly. Annie tried to breathe deeply. She let go his arms, and held his hands tightly instead. She looked into his face. ‘There is such a bond between us, Simon. We’ve fought together, and been through so much together. But Ragimund told me on the trireme, that she was afraid of me! I didn’t understand at the time, but now I do! She loves you very much, my brother. She was afraid that she might come between us, and break our bond!’ ‘She won’t and can’t’ Simon replied softly. ‘I’d go to the ends of the earth with you, Annie, if I had to’. ‘I know you would. And she told me other things as well. I understand now why she showed us those things in the forest. She was trying to show us her past, so that we would know. But she was telling us about herself, because she cared. She was frightened that we would think of her as someone who was ruthless and vicious. Both you and I know, she isn’t! I also know that she’s a faery and a warrior! But she’s also kind and gentle, warm and loving! That’s what she really is. Simon! I know that now!’ ‘I know that too’. Her brother replied quietly. ‘But why are you so worried about her now?’ ‘Because I’m frightened that she will go down into that dark terrible place that I went down into! She’s got no-one, Simon! Only you!’ She looked frantically again into his face, and tried to gather her voice. ‘I went into that dark hole, Simon. I nearly did again in Mila. But you and the others rescued me, and brought me back. I don’t want Ragimund to go down where I did! She deserves much more! Her own sisters turned their backs on her! I saw her face, Simon! She doesn’t deserve that! It was so cruel!’ They both looked up at the upper walls of the gatehouse, and saw Ragimund’s small dark figure, sitting crouched against the inner wall, her head down against her drawn-up knees. ‘Simon, bring her back! Don’t let her go down into that terrible darkness! She has no-one, except you! Please! Please, Simon. I’m begging you! Bring her back!’ She let go of his hands, her eyes wide and imploring. Her brother looked at her, with a look of such tenderness, that she felt she might nearly cry again. ‘Annie’. was all he said. Then he set off at a run along the wall and up the stone steps and the top of the gatehouse, where Ragimund crouched miserably. She saw him reach out for her hands. She thrust them away. Then her brother reached down and pulled her to her feet. He talked softly to her, though she could not hear the words at that distance. Then she saw the glow of happiness and joy in Ragimund’s face, and saw both the figures in the descending darkness hold each other tightly. She sank back down against the wall again, her sword catching for a moment, slung across her back. She looked back at the two figures, now clasping each others’ hands, exactly as she and her brother had done, a few moments ago. ‘Bless you Simon’, she whispered. ‘Bless you. Bless you both’. She pulled up her own knees, and sank her head down. She couldn’t cry any more, but she stayed there, not moving, deeply sad, but thankful that she had at least done something, to make her brother and his faery love happy. ************** She didn’t know how long she had been there, but she was suddenly aware of two figures slipping down each side of her. She reached instinctively for her sword behind her. ‘It’s all right. Annie’. one of the figures said quietly. ‘It’s only us’. She realised it was Indira and Pei-Ying. A third figure, who she now saw was Mariko, knelt down quietly in front, her bare knees against the cold stone pavement. ‘Just go away. Go away! Just piss off! I don’t need you!’ Annie cried furiously. ‘I want to be on my own!’ None of them moved. Pei-Ying, sitting on her right, said quietly ‘No, Annie. You do need us. We are not going away’. She reached out and pulled Annie’s chin up towards her, but Annie jerked her head away angrily. Pei-Ying pulled her head back towards her, with a strength that startled Annie. ‘Look at me!’ Annie stared back into her eyes. She had never fully realised how beautiful Pei-Ying’s eyes were. They were dark and bright, almost as if she could see herself in them. ‘Walk away from the darkness, Annie. Come back with us into the warm light’. Pei-Ying said very softly. Annie felt Indira’s soft fragrant hair on her shoulder, and her warm sweet breath. ‘You understand what we are saying to you, don’t you, Annie?’ she whispered. ‘Never go into that dark again. Promise us’. She felt a kind of peace descending on her, like warm dust, with the scent of pollen. ‘Yes, I promise’. ‘Thank goodness!’ said Indira, pulling herself upright. ‘ Annie!’ Her eyes were bright with tears. ‘Don’t ever go away from us again! I thought I’d lost you in Mila! I really did!’ ‘No’. said Annie sadly. ‘You won’t lose me again. But I’m sad and miserable and I don’t even know how to find my way home!’ Mariko stood before her, her hand reaching out. ‘Look out over this wall with me, Annie. One last time. Please’.’ She took Mariko’s outstretched hand, and got up stiffly. She leant against the wall, Mariko’s small slender fingers interlocked with hers, and looked out. Scores of small robed figures were moving around that landscape of the dead, and she realised, that these were the families of the Barbarossi, who had walked all the way from the hills to find their loved ones. She couldn’t hear them, but she saw their faces cry and wail in sorrow and grief. She saw a young boy, no more than seven years old, searching amongst the bodies. His mouth was open, crying out, as if he expected his dead father to answer him. Further along, to the right, a woman, her hands outstretched, fell back into the arms of her younger children, as she discovered the body of her son. The two young boys stumbled desperately as they tried to bear the weight of their grieving mother. Further to the right, a young girl was trying to push a small posy of flowers into her fallen father’s hands. She tried and tried, but her father’s hands were clenched in the rigor mortis of death. Eventually she gave up, and wept over his body, still clutching the flowers that she had picked for him. ‘You must stop this, Annie! You and Simon!. We will be with you, but only you two can stop this barbarity!’ Annie realised that Mariko was crying, deeply, soundlessly. There were tears trickling down her gentle cheeks. ‘Don’t cry, Mariko’. She said gently ‘There have been too many tears shed today’. Mariko looked out again. ‘If this does not stop, then there will be another battle, and another, and another and another, and more. Every battle, and the whole war, will create a trail of grief and sorrow that will affect generations to come. You can stop this, Annie! You and Simon! Only you have the reputation, the standing to do this! We will walk with you every step of the way! You know that! But you must at least try to put an end to this!’ ‘I don’t know how to!’ Annie cried miserably. ‘How do I stop this filthy, miserable, hideous war?’ Mariko looked at her, her face wet. ‘You and Simon will find a way. I know you will. I have faith in you’. ‘I will do my best. That is all I can do, Mariko’. Mariko smiled. ‘Then that is good enough for me. I have made a decision, Annie, but I will tell you when the time is right’. ‘What decision?’ asked Annie, startled. ‘Trust me, Annie, as I trust you’. Mariko turned and looked back over the wall, at the bright glimmer of torches below, where the Barbarossi were still gathering their dead. Annie sank down again between Pei-Ying and Indira, who moved closer to her. ‘Put your head down on my shoulder, Annie’. Indira whispered. ‘You need comforting. We all do. Let’s just stay here for a while’. Annir gratefully laid her head against Indira’s soft black hair, and closed her eyes. She felt Pei-Yings hand close gently around hers. Mariko continued to lean against the wall, looking out. The night gradually fell around them. ************** The faery walked along the wall holding a lighted torch in her left hand, anxiously looking for the humans that her commander had told her to find, to make sure that they were safe. She looked over to the gatehouse ahead of her. She saw one of the humans with her commander, sitting together, holding hands and talking softly to each other. She smiled gently. She walked on a few yards, her sword rustling, hard against her back. Then she stopped again and hesitated. In the light of her torch, she could see the other humans. They were sitting close together, nestling like young birds, their heads resting on each other’s shoulders. They looked peaceful, their backs resting on the hard black silhouette of the battlements, against the strange crimson glow of the night sky. She smiled again. Suddenly she felt deeply moved, and stifled a quiet sob. They reminded her so much of her own family, far away to the north, in Pulan. She moved quietly and softly, taking care that her boots would not wake them on the stones. Then she settled down, further along the wall, to watch over them, until they awoke.

Frank Jackson. 30/05/2011 (word count – 10882)

The plan of Cestmos.

|

|

BACK